肝细胞癌肝移植患者的选择

引言

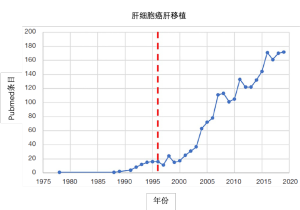

目前推荐肝移植用于不可切除的极早期(巴塞罗那肝癌分期BCLC-0)、早期(BCLC-A)、高选择性中期(BCLC-B)和进展期(BCLC-C/D)肝细胞癌(HCC)患者[1]。如果不经过严格的选择,肝移植在术后前几天就会给HCC患者带来灾难性后果。二十世纪八十年代,匹兹堡大学研究组针对非恶性肝病患者进行死者供体肝移植治疗,报道了令人鼓舞的结果,在外植体中偶然发现HCC[2,3]。根据该早期经验,以及HCC肝切除相关研究的结论[4,5],米兰研究组为不可切除HCC患者肝移植制定了第一个形态学选择标准,并证明了了单个病灶(≤5cm)或3个病灶以内(最大的≤3cm)患者肝移植后可以获得四年的生存期[6]。“米兰标准”急剧降低了HCC患者肝移植后的复发率,并引起随后十余年移植病例和相关文献发表数量的暴增(图1)。

然而,符合米兰标准的HCC患者肝移植术后仍存在较低的复发率,而对于超出米兰标准的经选择的患者,肝移植仍是最佳治疗方法。这些发现,与围手术期护理、影像学检查、外科技术和长程管理的改进一起,共同促成了移植适用标准的改良。本综述将简略总结近十年来,成年HCC患者肝移植的患者选择方面的最重要的临床进展。

死者供体肝移植

移植需要使用死者或活体捐献的器官。HCC活体肝移植(living donor liver transplantation,LDLT)将在另一部分讨论。死者供体肝移植用于HCC,减少了无癌症的终末期肝病患者的可用器官储备。HCC患者的病情进展风险,必须与终末期肝病患者的死亡风险相当,且5年存活率相当,才能获得死者供体肝脏。极早期HCC患者移植后表现出最高的5年存活率,然而,他们最不容易退出移植等待名单,且移植后的生存获益最低[7]。例如,单病灶≤3cm,肝导向治疗反应良好,且甲胎蛋白(alpha-fetoprotein,AFP)≤20ng/mL的患者,在肝导向治疗后,1年和2年的HCC进展风险仅比米兰标准分别高出1.6%和1.9%[8]。因此,即使5年存活率突出,这类患者优先获得死者供肝也是不合理的[9]。多种肿瘤生物学标志物已经用于预测移植后的HCC复发率和存活率,并促成了数个国家不同的死者供肝分配政策。其中纳入的许多风险因素都是微血管侵犯和(或)肿瘤低分化的间接标志物。国家选取标准的依据是器官供应-需求关系,在死者供体器官短缺的国家,使用的标准就更严苛,而在器官需求少和/或器官供应充足的国家,则更可能使用较宽松的标准。例如,美国在2002年开始采用米兰标准,并作为唯一标准持续使用15年,即使米兰研究组停止使用该标准数年后,且有更多证据支持放宽标准时,仍然没有改变。但是,对死者供肝的大量需求并不能证明修改为HCC患者分配供肝的标准是合理的,直到有证据表明,HCC患者远多于无癌症的的终末期肝病患者,才促使死者供肝分配系统显著改变。

肿瘤负荷

二十世纪九十年代后期和二十一世纪 ,随着各种各样的选择标准的制定,以肿瘤大小和肿瘤结节数量衡量的肿瘤负荷成为患者选择的基础,但这些标准可以而且应该扩大的限度尚不清楚。Markov模型表明,如果米兰标准以外的HCC患者肝移植术后预期5年总生存率<61%,则将死者供肝移植的肿瘤负荷标准扩大到米兰标准以外的不利影响将超过其获益[10]。

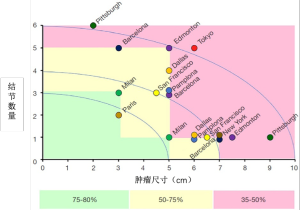

Metroticket国际数据库(图2)是一个里程碑式的研究,纳入9个国家的36个移植中心的1556位患者,结果发现,对于符合米兰标准的患者,微血管浸润和(或)低分化与肿瘤复发率不相关;但是,不符合米兰标准的肿瘤,微血管侵犯和(或)低分化导致更高的复发率[15]。这表明,除肿瘤负荷外,还需要其他生物标志物,且在移植前需要确定肿瘤分化程度和微血管侵犯情况,并将低分化和微血管侵犯作为HCC复发的主要预测因素和选择标准。该研究中,满足“极七”[HCC最大肿瘤的尺寸(cm)与肿瘤数量之和,比如一个6cm的肿瘤,1+6=7]标准的患者,5年存活率为71.2%(米兰标准为73.3%,P=NS)[15]。网上有基于该研究数据库的在线计算器(http://www.hcc-olt-metroticket.org/),可根据术前影像学表现和术后检查计算5年存活率。

血清AFP

血清AFP长期用作HCC的肿瘤标志物[16]。AFP最初是一个诊断/筛查工具,逐渐发展为一个肿瘤生物学的标志物,现在一些国家和地区把它纳入HCC患者肝移植的筛选标准。法国国家项目(French National Program)的一项分析表明,血清AFP水平与肿瘤负荷的相互作用是比米兰标准更好的HCC复发预测因子。符合米兰标准且AFP>1000ng/mL的患者有比米兰标准高出三倍的HCC复发风险,而超出米兰标准且AFP<100ng/mL的患者HCC复发率却与米兰标准类似[17]。血清AFP截断点选为>1000ng/mL,仅排除了4.7%的HCC患者,却降低20%的总体复发率[18]。在某个美国器官共享联合网络(UNOS)地区内,等待时间较长的符合米兰标准的患者中,AFP增长速率≥每月7.5 ng/mL与移植后微血管侵犯和HCC复发相关[19]。

一项对UNOS数据库内45267例患者的分析表明,血清AFP高于15 ng/mL与HCC患者移植后死亡风险的增加呈正相关,分组分析结果呈剂量依赖性:血清AFP 16~65 ng/mL,校正危险比=1.38;AFP 66~320 ng/mL,校正危险比=1.65;AFP>320 ng/mL,校正危险比=2.37[20]。超出米兰标准且血清AFP 0~15 ng/mL的HCC患者,与无HCC的患者存活率类似,而符合米兰标准且血清AFP≥66 ng/mL的患者与无HCC的患者相比,移植后死亡风险增加(校正危险比=1.93)。此外,在等待供体期间接受肝脏导向治疗后血清AFP水平下降(从>320到≤320,或从16~320到0~15 ng/mL)的患者,移植后死亡风险不增加。相比之下,血清AFP水平升高(从0~15到≥16 ng/mL,或从16~320到>320 ng/mL)的患者,移植后的死亡风险显著高于无HCC 的患者[20]。由同一通讯作者对器官移植受者科学登记处(Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients)进行的两项独立分析发现,血清AFP截断值设定为为400 ng/mL时,移植后HCC复发风险的曲线下面积为0.7[21-23],并由此来判断移植后HCC复发风险。中国的一个移植中心也使用了相同的截断值[24]。即使血清AFP初始水平为≥1000 ng/mL,血清AFP>400 ng/mL但在肝导向治疗后降至≤400 ng/mL的患者,退出率和3年生存率与初始AFP≤400 ng/mL的患者相似[23]。

根据上述数据,UNOS修改了与AFP相关的HCC豁免(exception point)标准。病变符合米兰标准,但AFP超过1000的候选人最初没有资格获得MELD豁免。肝导向治疗后AFP<500的候选人可获得MELD豁免。在肝导向治疗后,候选人一旦AFP≥500,就要提交国家审查委员会(National Review Board)[25]。

另一个包含7491例肝癌患者的UNOS数据库研究,分析了MELD评分、血清AFP水平、病灶数量和最大肿瘤大小之间的相互作用[26]。该研究表明,血清AFP是肝移植术后存活率的独立预测因子,与肝功能(MELD)、肿瘤负荷结合起来,有助于平衡等待名单中HCC患者和终末期肝病患者的优先级[26]。作者将该指标命名为“MELDEQ评分”,但像其他关于HCC的改良版MELD评分一样,该评分尚未纳入国家分配政策[27-31]。

Mazzafero领导了一个两国研究小组,这个小组于2018年更新了Metroticket标准(2.0版)[32]。通过对来自3个意大利肝移植中心的训练数据集进行竞争性风险回归分析表明,肿瘤数量加大小(cm)的总和以及AFP血清水平,与HCC相关的死亡显著相关。对于移植后5年HCC相关存活率为70%的HCC患者,其AFP应<200 ng/mL,肿瘤数量和最大尺寸之和不应超过7;如果AFP为200~400 ng/mL,则肿瘤的数量和大小之和应≤5;如果AFP为400~1000 ng/mL,则肿瘤数量和最大尺寸之和应≤4。该模型经中国的一个队列研究验证,准确率为72%[32]。

与HCC患者移植后5年生存率降低相关的其他血清标志物包括:中性粒细胞与淋巴细胞比率>5,AFP-L3>35%,脱-γ-羧基凝血酶原>7.5 ng/mL或≤400 mAU/mL[33-35]。然而,这些替代性血清标志物均未被广泛使用。

影像学表现

影像学研究十分适用于HCC患者肝移植的评估。有几项研究评估了影像学表现与HCC复发率、微血管侵犯的相关性。

三种CT表现的组合与微血管侵犯相关[36]。这三种表现是:在静脉期肿瘤内持续存在离散性动脉强化;部分或完全包围肿瘤的低密度边缘;肿瘤内无动脉低密度晕时,肿瘤与邻近肝实质之间的局灶性或环绕性衰减速率的急剧衰减。这三种表现在预测微血管浸润方面,准确性、敏感性和特异性分别为89%、76%和94%[36]。

使用钆塞酸造影剂对比增强的磁共振成像表现与微血管侵犯、早期HCC复发相关:瘤周动脉增强、肿瘤边缘不光滑和肝胆期瘤周低信号。有两个或三个上述表现的患者,早期复发率高于无上述表现的患者(27.9% vs. 12.6%)[37]。

不推荐将氟脱氧葡萄糖(18FDG)正电子发射断层CT常规用于HCC分期,然而,一些研究表明,高代谢性HCC与外植体微血管侵犯、HCC早期复发和肝外转移的高风险相关[38-43]。

移植前活检

中国、意大利和加拿大的移植中心已将肿瘤分化情况作为HCC行肝移植治疗的患者选择标准[24,44]。多伦多研究组制定了一项选择HCC患者的策略,不考虑病灶的大小和数量[45]。将有癌症相关症状和(或)术前经皮肝活检发现低分化或未分化肿瘤的患者排除在外,并在等待供肝期间对高分化或中分化肿瘤患者进行积极的肝导向治疗。尽管最初的报告令人鼓舞[46],但与符合米兰标准的患者相比,候选者的退出率更高,意向性治疗的5年和10年生存率更低。然而,与无癌症的终末期肝病患者相比,存活率仍然可以接受,但术前活检与外植体研究的相关性相对较差[47],加拿大的国家/地区分配政策已发生变化,阻止该策略的进一步发展[48]。

肝导向治疗效果

局部区域治疗有多种选择,这些局部治疗被归类为肝导向治疗,包括几种形式的消融治疗(射频、微波、冷冻、不可逆电穿孔)、经动脉治疗(经动脉化疗栓塞、经动脉放射栓塞),和放射治疗(立体定向放射治疗、质子束治疗)。肝导向治疗的效果可预测肝移植的治疗效果[49-51]。肝导向治疗后病情稳定或进展的患者,复发风险是部分或完全缓解患者的3倍(17.6% vs. 5.3%,P=0.014)[52]。肝导向治疗对移植后HCC复发的影响与治疗反应有关,而与治疗次数无关[53]。即使肝导向治疗作为肝移植的桥梁对退出率的影响证据有限[54],大多数移植中心仍为等待死者供体肝脏的患者提供肝导向治疗。不同移植中心中,肝导向疗法的选择存在显著的异质性。一些中心倡导经动脉化疗栓塞术,因为消融术有针道肿瘤种植的风险[55];其他中心倡导尽可能做经皮消融术,因为化疗栓塞术有损伤动脉的风险[56,57];而一些中心主张采用一种特殊形式的放射治疗,因为其长期效果较好[58];还有另一些中心主张采用多种技术进行积极治疗[59]。肝导向疗法应根据患者的肿瘤负荷和肝功能而定,因为大多数肝导向疗法仅推荐用于胆红素<3 mg/dL的Child A或B级患者。

美国UNOS各地区之间死者供体肝脏利用情况有所不同,导致了登记和肝移植之间等待时间较短的患者,在移植后表现出较高的HCC复发风险[60]。在等待时间较长的地区观察到的情况正好相反,这些地区由于HCC进展而导致退出率较高,但接受移植的患者HCC复发率较低,且存活率较高[61]。这种现象被解读为一种“时间检验”,即生物学表现不良的患者在等待时间内病情进展,而生物学表现良好的患者等待期间在接受肝导向治疗后仍能进行肝移植,这一指标已成为肿瘤生物学的一个标志物。等待时间过长可能导致HCC进展,因而超出移植标准。来自美国3个中心的多中心分析表明,与等待时间6~18个月相比,等待时间少于6 个月和超过18个月与移植后1年和5年HCC复发风险增加相关(分别为6.4%和15.5% vs. 4.5%和9.8%,P=0.049)[62]。这些观察结果导致了美国HCC国家分配制度的变化。

一项UNOS数据库分析回顾了登记肝移植的HCC患者肿瘤负荷的初始值、最大值和最后值[63]。肿瘤负荷分级为:A级,单个HCC<2 cm;B级,符合米兰标准的HCC;C级,超出米兰标准,但符合UCSF标准;D级,超出米兰和UCSF标准。肝导向治疗效果对于HCC患者肝移植后的复发风险至关重要[63]。作者利用自己的数据,开发了一个在线计算器(https://clifeuw.org/rhiml/),可用于日常决策。

“降期”

为了符合米兰标准而“降期”的理念在文献中已多有讨论,但是,肝导向治疗诱导HCC的部分或完全反应后,肿瘤的分期没有改动,而只有肿瘤负荷下降,因此,正确的术语是“降尺寸”[64]。尽管一些研究组提出,采用特定策略获得较高成功率和较低复发率[65],但肝导向治疗后,就获得部分或完全缓解和肿瘤负荷下降到满足米兰标准而言,似乎并无差别[64]。UNOS已经根据旧金山加利福尼亚大学研究组的经验为这些患者建立了选择标准[66]:单病灶>5 cm且≤8 cm;2到3个病灶,至少一个>3 cm且≤5 cm,且肿瘤总直径≤8 cm;4到5个病灶均≤3 cm,且肿瘤总直径≤8 cm。一项纳入3819名患者的UNOS数据库分析中,Mehta等人发现,接受减小肿瘤尺寸治疗的患者中,422名符合UNOS标准,121名不符合UNOS标准[67]。符合UNOS缩小尺寸标准的患者与符合米兰标准的患者相比,3年存活率没有差异(79.1% vs. 83.2%,P=NS),而不符合UNOS标准的患者3年存活率明显偏低(71.4%,P=0.04)。然而,移植前接受缩小尺寸治疗的患者HCC复发的风险较高,不符合标准的患者复发风险更高(米兰标准6.9%,UNOS标准12.8%,不符合标准16.7%)。仅考虑符合UNOS标准的患者,等待时间较长地区的3年生存率较高(中位时间>9个月的地区为92.3%,中位时间<3个月的地区为78.7%)[67]。

肿瘤总体积已替代结节数量和大小,成为肿瘤负荷选择标准,把≤115 cm3作为截断值,相当于6 cm的单病灶[68]。超出米兰标准的患者有较高的退出率和较低的意向性治疗存活率,但肝移植后的存活率相似[68]。加拿大五个地区中有三个采用了肝总体积/AFP标准来为HCC患者分配死者供体肝脏,第四个地区(安大略省)修改了该标准(肝总体积<145 cm3,且AFP<1000 ng/mL)[48]。

死亡供肝移植患者选择的前景

2000年代末,阿根廷采用了美国的死者供肝分配模式。这一经验为具有不同捐赠动态和资源可用度的国家(或地区)借用肝脏分配系统提供了前车之鉴。MELD评分方法实施后,等待期患者死亡率上升(尤其是MELD评分较低的慢性肝病患者),而HCC患者有最高的移植率(高达84%,而MELD评分低的慢性肝病患者仅为3%)[69]。尽管等待期死亡率的增加可能是多因素的相互作用的结果,但相同现象也出现在美国的HCC患者中,这种死亡率的增加通过对满足豁免标准的HCC患者使用MELD评分中位数而导致了分配系统的改变[25]。

HCC进展至超出移植标准的风险、HCC肝移植后患者的5年生存率一直是确定死者供肝分配的参考指标。然而,越来越清楚的是,较小/较早期肿瘤患者的5年生存率很高,但移植后生存获益低,甚至没有。相反,较大、更晚期肿瘤患者移植后5年生存率较低,但总体生存获益较高。对来自5个欧洲国家10个移植中心的2103名患者的前瞻性意向治疗分析阐明了HCC患者肝移植的生存获益中,年龄、HCC相关标准(米兰标准、血清AFP和 肝导向治疗效果)、终末期肝病严重程度(MELD评分)和等待时间之间的相互作用[70]。该研究发现,有3或4个因素(生物学MELD评分≤13、符合米兰标准的HCC患者、肝导向治疗效果良好或疾病进展、AFP≥1000 ng/mL)的患者没有生存获益,而有2个、1个和无风险因素的患者则分别有20、40和60个月的生存活获益,据此提出了等待名单上的HCC患者不同级别的移植优先级,甚至踢出名单[70]。例如,符合米兰标准、肝导向疗法效果良好、生物MELD评分≤13的患者将被除名,而不符合米兰标准、肝导向治疗有部分反应、生物MELD评分>13、AFP<1000 ng/mL的患者,将以最高优先级获得死者供体肝脏。另一方面,不符合米兰标准、肝导向治疗后病情进展、AFP≥1000 ng/mL的患者将被除名,而符合米兰标准、肝导向治疗后病情稳定、MELD评分>13、AFP<1000 ng/mL的患者,也将以最高优先级获得死者供体肝脏[70]。

由于证据渐增,在接下来的十年里,全球范围内死者供肝分配政策可能发生变化,将更偏好生存获益与5年存活率的结合,而不仅仅是5年存活率。

肝细胞癌的活体肝移植

基于肿瘤负荷和肿瘤生物学标志物用于死者供体肝移植的选择标准,证据可靠。如前所述,死者供体肝脏的分配标准是强制性的,这样才可以在资源稀缺情况下为所选患者谋取最大化利益,同时维持对等候名单中无癌症的患者的公正性。然而,这些原则不适用于活体肝移植,因为捐赠的活体器官要用于特定受体。这种情况引起了关于HCC患者活体肝移植的争议,各移植中心采用了不同的选择标准。有一份全面的肝移植补充文件专门用于分析该问题[71-73]。一些作者建议容忍活体肝移植“轻微”的获益降低(预期5年存活率为40%)[74]。在移植外科医生中开展的一项调查表明,他们要求至少79%的预计1年存活率[75],然而,在活体供肝候选人中进行的调查显示,他们可接受的移植存活时间低至6个月[76]。作者认为,移植中心应该对死者供体肝移植和活体肝移植采用相同的标准。HCC患者活体肝移植的伦理原则与其他任何进行肝移植的伦理原则相同。在某些情况下,移植中心的选择标准将超出国家政策设置的死者供肝分配标准,以便于一致地向患者提供活体肝移植。

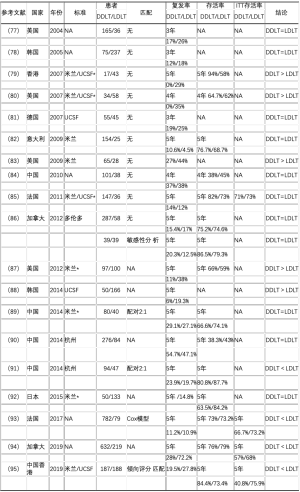

活体肝移植与死者供者移植对比

死者供体肝移植和活体肝移植之间的逻辑差异和HCC患者选择标准的异质性,使得难以比较其结局。许多研究者对此进行过分析(表1),不幸的是,许多研究都存在方法学问题。没有评估该问题的前瞻性研究,且大多数回顾性研究都没有根据受体或HCC相关特征匹配患者。三项荟萃分析探讨了每种策略对HCC复发的影响(包括7~29项回顾性研究),得到了不同的结果[96-98]。进行恰当匹配的研究发现,死者供体肝移植和活体肝移植后HCC复发率类似,而意向治疗研究表明,活体肝移植的存活率类似或优于死者供肝移植[85,86,93-95]。

Full table

活体肝移植肿瘤负荷选择标准

在活体肝移植中,供肝随时可用,可在供体和受体检查完成后迅速移植。这引起了关于观察期益处的争议,观察期在死者供肝移植里已有描述[99]。而一些活体肝移植研究组担心,经动脉的肝导向治疗后出现动脉并发症风险高[100]。对经动脉化疗栓塞后接受活体肝移植的HCC患者的一项回顾性分析表明,在至少2个月的观察期后,部分或完全缓解的患者,移植后存活率有提高[101]。然而,对于是否延迟活体肝移植以评估肝导向治疗效果,目前尚无共识[102]。

在日本,HCC肝移植的选择标准是根据机构和地区经验制定的。东京大学报告,结节≤5个、均不大于5 cm(即“5-5规则”)的患者活体肝移植后5年存活 率为75%[103-105]。京都大学设置了一个综合标准,要求肿瘤总数≤10、长径均≤5 cm、血清脱-γ-羧基凝血酶原≤400 mAU/mL,该标准获得了7%的5年HCC复发率,和82%的5年存活率[35]。

在韩国,活体肝移植适用于所有无远处转移的HCC患者。首尔的一个移植中心将活体肝移植扩展到“极晚期”HCC,该中心超过50%的活体肝移植用于HCC患者[106]。韩国国家癌症中心结合肿瘤负荷(病灶直径总和≤10 cm)、高代谢肿瘤,提出了HCC活体肝移植的专门标准[107]。根据该标准,无桥接治疗或降期治疗的情况下,活体肝移植在分期后15天内进行。280例活体肝移植的初步经验表明,符合该标准的患者存活率与米兰标准相似,而符合米兰标准且有高代谢肿瘤的患者生存率有下降趋势[108]。

独特的肝细胞癌活体肝移植经验

大血管侵犯在大多数西方移植中心是禁忌证,然而,在东方移植中心首次经验后,西方移植中心的相关报道正在涌现。来自韩国不同中心的三项研究报告了伴有大血管侵犯的HCC患者活体肝移植。三项研究中有两项确认,门静脉主干癌栓是HCC复发和存活率不良的危险因素,肿瘤侵犯门静脉节段分支对预后影响有限[109,110]。这三项研究确定了一些血清标志物,可能在选择伴有大血管侵犯的HCC患者进行移植时发挥作用[109-111]。

一项多中心、国际性、回顾性研究评估了30例伴有大血管侵犯、在肝导向治疗成功后进行移植的HCC患者,发现5年复发率为45.7%,5年存活率为59.7%。对肝导向治疗有反应,且治疗后、移植前血清AFP≤10 ng/mL的患者,复发率为11.1%,5年存活率为83.3%[112]。

胆管癌栓罕见,与肿瘤低分化、微血管侵犯和大血管侵犯有关。纳入11项研究的两个荟萃分析发现,与无胆管癌栓的患者相比,有胆管癌栓的患者切除术后有相似的短期预后(1年和3年存活率),但长期存活率较低(平均相差20个月)[113,114]。最近,一项来自韩国和日本的多中心研究表明,伴有胆管癌栓的HCC患者肝切除术后的预后受当时分期和基础肝功能的影响,提示胆管侵犯对存活率的影响不如血管侵犯突出[115]。伴胆管癌栓的HCC患者肝移植经验非常有限,主要局限于东方移植中心的活体肝移植。韩国报道了包含8例和14例患者的2项观察性研究(仅1例是死者供肝移植),观察到5年复发率为46.2%~75%,5年存活率为50%[116,117]。

与死者供肝移植类似,血清标志物已用于预测活体肝移植后HCC的复发,但尚未广泛应用[118-120]。据报道,与活体肝移植后HCC复发相关的其他因素包括,男性供体、供体胆红素升高和受体血小板升高,但这些统计相关性的因果关系尚不清楚[121-123]。

结论

肿瘤负荷、血清标志物(AFP)、影像学检查和肝导向治疗效果有可靠的数据支撑,各国可根据自身肝源情况,赖之以为分配死者供肝的选择标准。未来十年里,这些标准可能会继续发展,将生存收益包含进来,作为5年存活率以外的一个变量。通过肝导向治疗将HCC尺寸缩小到米兰标准,逐渐为世人所广泛接受。活体肝移植为低捐肝率和(或)HCC高发病率地区的HCC患者提供了一个可行的选择,且有与死者供肝移植相似的复发率和同等(可能更高)的意向治疗存活率。伴有肝硬化的成年HCC患者做肝移植评估的数据,不能外推到肝脏正常的成年患者和(或)儿童患者。

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Provenance and Peer Review: This article was commissioned by the Guest Editor (Nahum Méndez-Sánchez) for the series “Current Status and Future Expectations in the Management of Gastrointestinal Cancer” published in Digestive Medicine Research. The article has undergone external peer review.

Peer Review File: Available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/dmr-20-115

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/dmr-20-115). The series “Current Status and Future Expectations in the Management of Gastrointestinal Cancer” was commissioned by the editorial office without any funding or sponsorship. The authors have no other conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Zamora-Valdes D, Taner T, Nagorney DM. Surgical Treatment of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cancer Control 2017;24:1073274817729258. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Iwatsuki S, Gordon RD, Shaw BW Jr, et al. Role of liver transplantation in cancer therapy. Ann Surg 1985;202:401-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Esquivel CO, Mieles L, Marino IR, et al. Liver transplantation for hereditary tyrosinemia in the presence of hepatocellular carcinoma. Transplant Proc 1989;21:2445-6. [PubMed]

- Iwatsuki S, Starzl TE, Sheahan DG, et al. Hepatic resection versus transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann Surg 1991;214:221-8; discussion 228-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bismuth H, Chiche L, Adam R, et al. Liver resection versus transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhotic patients. Ann Surg 1993;218:145-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mazzaferro V, Regalia E, Doci R, et al. Liver transplantation for the treatment of small hepatocellular carcinomas in patients with cirrhosis. N Engl J Med 1996;334:693-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Vitale A, Morales RR, Zanus G, et al. Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer staging and transplant survival benefit for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: a multicentre, cohort study. Lancet Oncol 2011;12:654-62. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mehta N, Dodge JL, Goel A, et al. Identification of liver transplant candidates with hepatocellular carcinoma and a very low dropout risk: implications for the current organ allocation policy. Liver Transpl 2013;19:1343-53. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mehta N, Dodge JL, Hirose R, et al. Predictors of low risk for dropout from the liver transplant waiting list for hepatocellular carcinoma in long wait time regions: Implications for organ allocation. Am J Transplant 2019;19:2210-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Volk ML, Vijan S, Marrero JA. A novel model measuring the harm of transplanting hepatocellular carcinoma exceeding Milan criteria. Am J Transplant 2008;8:839-46. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mazzaferro V. Results of liver transplantation: with or without Milan criteria? Liver Transpl 2007;13:S44-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kneteman NM, Oberholzer J, Al Saghier M, et al. Sirolimus-based immunosuppression for liver transplantation in the presence of extended criteria for hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Transpl 2004;10:1301-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Onaca N, Davis GL, Goldstein RM, et al. Expanded criteria for liver transplantation in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: a report from the International Registry of Hepatic Tumors in Liver Transplantation. Liver Transpl 2007;13:391-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Llovet JM, Pavel M, Rimola J, et al. Pilot study of living donor liver transplantation for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma exceeding Milan Criteria (Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer extended criteria). Liver Transpl 2018;24:369-79. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mazzaferro V, Llovet JM, Miceli R, et al. Predicting survival after liver transplantation in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma beyond the Milan criteria: a retrospective, exploratory analysis. Lancet Oncol 2009;10:35-43. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mak LY, Cruz-Ramon V, Chinchilla-Lopez P, et al. Global Epidemiology, Prevention, and Management of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book 2018;38:262-79. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Duvoux C, Roudot-Thoraval F, Decaens T, et al. Liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma: a model including alpha-fetoprotein improves the performance of Milan criteria. Gastroenterology 2012;143:986-94.e3; quiz e14-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hameed B, Mehta N, Sapisochin G, et al. Alpha-fetoprotein level > 1000 ng/mL as an exclusion criterion for liver transplantation in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma meeting the Milan criteria. Liver Transpl 2014;20:945-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Giard JM, Mehta N, Dodge JL, et al. Alpha-Fetoprotein Slope >7.5 ng/mL per Month Predicts Microvascular Invasion and Tumor Recurrence After Liver Transplantation for Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Transplantation 2018;102:816-22. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Berry K, Ioannou GN. Serum alpha-fetoprotein level independently predicts posttransplant survival in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Transpl 2013;19:634-45. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Toso C, Trotter J, Wei A, et al. Total tumor volume predicts risk of recurrence following liver transplantation in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Transpl 2008;14:1107-15. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Toso C, Asthana S, Bigam DL, et al. Reassessing selection criteria prior to liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma utilizing the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients database. Hepatology 2009;49:832-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Merani S, Majno P, Kneteman NM, et al. The impact of waiting list alpha-fetoprotein changes on the outcome of liver transplant for hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol 2011;55:814-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zheng SS, Xu X, Wu J, et al. Liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma: Hangzhou experiences. Transplantation 2008;85:1726-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Heimbach JK. Evolution of Liver Transplant Selection Criteria and U.S. Allocation Policy for Patients with Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Semin Liver Dis 2020; [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Marvin MR, Ferguson N, Cannon RM, et al. MELDEQ: An alternative Model for End-Stage Liver Disease score for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Transpl 2015;21:612-22. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Piscaglia F, Camaggi V, Ravaioli M, et al. A new priority policy for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma awaiting liver transplantation within the model for end-stage liver disease system. Liver Transpl 2007;13:857-66. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sasaki K, Firl DJ, Hashimoto K, et al. Development and validation of the HALT-HCC score to predict mortality in liver transplant recipients with hepatocellular carcinoma: a retrospective cohort analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017;2:595-603. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Freeman RB, Edwards EB, Harper AM. Waiting list removal rates among patients with chronic and malignant liver diseases. Am J Transplant 2006;6:1416-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Toso C, Dupuis-Lozeron E, Majno P, et al. A model for dropout assessment of candidates with or without hepatocellular carcinoma on a common liver transplant waiting list. Hepatology 2012;56:149-56. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Vitale A, Volk ML, De Feo TM, et al. A method for establishing allocation equity among patients with and without hepatocellular carcinoma on a common liver transplant waiting list. J Hepatol 2014;60:290-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mazzaferro V, Sposito C, Zhou J, et al. Metroticket 2.0 Model for Analysis of Competing Risks of Death After Liver Transplantation for Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Gastroenterology 2018;154:128-39. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Halazun KJ, Najjar M, Abdelmessih RM, et al. Recurrence After Liver Transplantation for Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A New MORAL to the Story. Ann Surg 2017;265:557-64. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chaiteerakij R, Zhang X, Addissie BD, et al. Combinations of biomarkers and Milan criteria for predicting hepatocellular carcinoma recurrence after liver transplantation. Liver Transpl 2015;21:599-606. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kaido T, Ogawa K, Mori A, et al. Usefulness of the Kyoto criteria as expanded selection criteria for liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma. Surgery 2013;154:1053-60. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Banerjee S, Wang DS, Kim HJ, et al. A computed tomography radiogenomic biomarker predicts microvascular invasion and clinical outcomes in hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 2015;62:792-800. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lee S, Kim SH, Lee JE, et al. Preoperative gadoxetic acid-enhanced MRI for predicting microvascular invasion in patients with single hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol 2017;67:526-34. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Morio K, Kawaoka T, Aikata H, et al. Preoperative PET-CT is useful for predicting recurrent extrahepatic metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma after resection. Eur J Radiol 2020;124:108828. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lim C, Salloum C, Chalaye J, et al. 18F-FDG PET/CT predicts microvascular invasion and early recurrence after liver resection for hepatocellular carcinoma: A prospective observational study. HPB (Oxford) 2019;21:739-47. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lin CY, Liao CW, Chu LY, et al. Predictive Value of 18F-FDG PET/CT for Vascular Invasion in Patients With Hepatocellular Carcinoma Before Liver Transplantation. Clin Nucl Med 2017;42:e183-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kim YI, Paeng JC, Cheon GJ, et al. Prediction of Posttransplantation Recurrence of Hepatocellular Carcinoma Using Metabolic and Volumetric Indices of 18F-FDG PET/CT. J Nucl Med 2016;57:1045-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kornberg A, Freesmeyer M, Barthel E, et al. 18F-FDG-uptake of hepatocellular carcinoma on PET predicts microvascular tumor invasion in liver transplant patients. Am J Transplant 2009;9:592-600. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kornberg A, Kupper B, Tannapfel A, et al. Patients with non-[18 F]fludeoxyglucose-avid advanced hepatocellular carcinoma on clinical staging may achieve long-term recurrence-free survival after liver transplantation. Liver Transpl 2012;18:53-61. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cillo U, Vitale A, Grigoletto F, et al. Intention-to-treat analysis of liver transplantation in selected, aggressively treated HCC patients exceeding the Milan criteria. Am J Transplant 2007;7:972-81. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- DuBay D, Sandroussi C, Sandhu L, et al. Liver transplantation for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma using poor tumor differentiation on biopsy as an exclusion criterion. Ann Surg 2011;253:166-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sapisochin G, Goldaracena N, Laurence JM, et al. The extended Toronto criteria for liver transplantation in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: A prospective validation study. Hepatology 2016;64:2077-88. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Court CM, Harlander-Locke MP, Markovic D, et al. Determination of hepatocellular carcinoma grade by needle biopsy is unreliable for liver transplant candidate selection. Liver Transpl 2017;23:1123-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Brahmania M, Marquez V, Kneteman NM, et al. Canadian liver transplant allocation for hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol 2019;71:1058-60. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- DiNorcia J, Florman SS, Haydel B, et al. Pathologic Response to Pretransplant Locoregional Therapy is Predictive of Patient Outcome After Liver Transplantation for Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Analysis From the US Multicenter HCC Transplant Consortium. Ann Surg 2020;271:616-24. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Agopian VG, Morshedi MM, McWilliams J, et al. Complete pathologic response to pretransplant locoregional therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma defines cancer cure after liver transplantation: analysis of 501 consecutively treated patients. Ann Surg 2015;262:536-45; discussion 543-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Agopian VG, Harlander-Locke MP, Ruiz RM, et al. Impact of Pretransplant Bridging Locoregional Therapy for Patients With Hepatocellular Carcinoma Within Milan Criteria Undergoing Liver Transplantation: Analysis of 3601 Patients From the US Multicenter HCC Transplant Consortium. Ann Surg 2017;266:525-35. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kim DJ, Clark PJ, Heimbach J, et al. Recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma: importance of mRECIST response to chemoembolization and tumor size. Am J Transplant 2014;14:1383-90. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Terzi E, Ray Kim W, Sanchez W, et al. Impact of multiple transarterial chemoembolization treatments on hepatocellular carcinoma for patients awaiting liver transplantation. Liver Transpl 2015;21:248-57. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tan CHN, Yu Y, Tan YRN, et al. Bridging therapies to liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma: A bridge to nowhere? Ann Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg 2018;22:27-35. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Francica G. Needle track seeding after radiofrequency ablation for hepatocellular carcinoma: prevalence, impact, and management challenge. J Hepatocell Carcinoma 2017;4:23-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wallace D, Cowling TE, Walker K, et al. Liver transplantation outcomes after transarterial chemotherapy for hepatocellular carcinoma. Br J Surg 2020;107:1183-91. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sneiders D, Houwen T, Pengel LHM, et al. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Posttransplant Hepatic Artery and Biliary Complications in Patients Treated With Transarterial Chemoembolization Before Liver Transplantation. Transplantation 2018;102:88-96. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gabr A, Kulik L, Mouli S, et al. Liver Transplantation Following Yttrium-90 Radioembolization: 15-year Experience in 207-Patient Cohort. Hepatology 2020; [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Onaca N, Klintmalm GB. Liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma: the Baylor experience. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci 2010;17:559-66. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Schlansky B, Chen Y, Scott DL, et al. Waiting time predicts survival after liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma: a cohort study using the United Network for Organ Sharing registry. Liver Transpl 2014;20:1045-56. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Halazun KJ, Patzer RE, Rana AA, et al. Standing the test of time: outcomes of a decade of prioritizing patients with hepatocellular carcinoma, results of the UNOS natural geographic experiment. Hepatology 2014;60:1957-62. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mehta N, Heimbach J, Lee D, et al. Wait Time of Less Than 6 and Greater Than 18 Months Predicts Hepatocellular Carcinoma Recurrence After Liver Transplantation: Proposing a Wait Time "Sweet Spot". Transplantation 2017;101:2071-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Vutien P, Dodge J, Bambha KM, et al. A Simple Measure of Hepatocellular Carcinoma Burden Predicts Tumor Recurrence After Liver Transplantation: The Recurrent Hepatocellular Carcinoma-Initial, Maximum, Last Classification. Liver Transpl 2019;25:559-70. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Parikh ND, Waljee AK, Singal AG. Downstaging hepatocellular carcinoma: A systematic review and pooled analysis. Liver Transpl 2015;21:1142-52. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lewandowski RJ, Kulik LM, Riaz A, et al. A comparative analysis of transarterial downstaging for hepatocellular carcinoma: chemoembolization versus radioembolization. Am J Transplant 2009;9:1920-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yao FY, Mehta N, Flemming J, et al. Downstaging of hepatocellular cancer before liver transplant: long-term outcome compared to tumors within Milan criteria. Hepatology 2015;61:1968-77. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mehta N, Dodge JL, Grab JD, et al. National Experience on Down-Staging of Hepatocellular Carcinoma Before Liver Transplant: Influence of Tumor Burden, Alpha-Fetoprotein, and Wait Time. Hepatology 2020;71:943-54. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Toso C, Meeberg G, Hernandez-Alejandro R, et al. Total tumor volume and alpha-fetoprotein for selection of transplant candidates with hepatocellular carcinoma: A prospective validation. Hepatology 2015;62:158-65. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- McCormack L, Gadano A, Lendoire J, et al. Model for end-stage liver disease-based allocation system for liver transplantation in Argentina: does it work outside the United States? HPB (Oxford) 2010;12:456-64. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lai Q, Vitale A, Iesari S, et al. Intention-to-treat survival benefit of liver transplantation in patients with hepatocellular cancer. Hepatology 2017;66:1910-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Grant D, Fisher RA, Abecassis M, et al. Should the liver transplant criteria for hepatocellular carcinoma be different for deceased donation and living donation? Liver Transpl 2011;17:S133-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Greig PD, Geier A, D'Alessandro AM, et al. Should we perform deceased donor liver transplantation after living donor liver transplantation has failed? Liver Transpl 2011;17:S139-46. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pomfret EA, Lodge JP, Villamil FG, et al. Should we use living donor grafts for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma? Ethical considerations. Liver Transpl 2011;17:S128-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lieber SR, Schiano TD, Rhodes R. Should living donor liver transplantation be an option when deceased donation is not? J Hepatol 2018;68:1076-82. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cotler SJ, Cotler S, Gambera M, et al. Adult living donor liver transplantation: perspectives from 100 liver transplant surgeons. Liver Transpl 2003;9:637-44. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Molinari M, Matz J, DeCoutere S, et al. Live liver donors' risk thresholds: risking a life to save a life. HPB (Oxford) 2014;16:560-74. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gondolesi GE, Roayaie S, Munoz L, et al. Adult living donor liver transplantation for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: extending UNOS priority criteria. Ann Surg 2004;239:142-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hwang S, Lee SG, Joh JW, et al. Liver transplantation for adult patients with hepatocellular carcinoma in Korea: comparison between cadaveric donor and living donor liver transplantations. Liver Transpl 2005;11:1265-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lo CM, Fan ST, Liu CL, et al. Living donor versus deceased donor liver transplantation for early irresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Br J Surg 2007;94:78-86. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fisher RA, Kulik LM, Freise CE, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma recurrence and death following living and deceased donor liver transplantation. Am J Transplant 2007;7:1601-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sotiropoulos GC, Lang H, Nadalin S, et al. Liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma: University Hospital Essen experience and metaanalysis of prognostic factors. J Am Coll Surg 2007;205:661-75. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Di Sandro S, Slim AO, Giacomoni A, et al. Living donor liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma: long-term results compared with deceased donor liver transplantation. Transplant Proc 2009;41:1283-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Vakili K, Pomposelli JJ, Cheah YL, et al. Living donor liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma: Increased recurrence but improved survival. Liver Transpl 2009;15:1861-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Li C, Wen TF, Yan LN, et al. Outcome of hepatocellular carcinoma treated by liver transplantation: comparison of living donor and deceased donor transplantation. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int 2010;9:366-9. [PubMed]

- Bhangui P, Vibert E, Majno P, et al. Intention-to-treat analysis of liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma: living versus deceased donor transplantation. Hepatology 2011;53:1570-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sandhu L, Sandroussi C, Guba M, et al. Living donor liver transplantation versus deceased donor liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma: comparable survival and recurrence. Liver Transpl 2012;18:315-22. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kulik LM, Fisher RA, Rodrigo DR, et al. Outcomes of living and deceased donor liver transplant recipients with hepatocellular carcinoma: results of the A2ALL cohort. Am J Transplant 2012;12:2997-3007. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Park MS, Lee KW, Suh SW, et al. Living-donor liver transplantation associated with higher incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma recurrence than deceased-donor liver transplantation. Transplantation 2014;97:71-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wan P, Zhang JJ, Li QG, et al. Living-donor or deceased-donor liver transplantation for hepatic carcinoma: a case-matched comparison. World J Gastroenterol 2014;20:4393-400. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Xiao GQ, Song JL, Shen S, et al. Living donor liver transplantation does not increase tumor recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma compared to deceased donor transplantation. World J Gastroenterol 2014;20:10953-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chen J, Xu X, Wu J, et al. The stratifying value of Hangzhou criteria in liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma. PLoS One 2014;9:e93128. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ninomiya M, Shirabe K, Facciuto ME, et al. Comparative study of living and deceased donor liver transplantation as a treatment for hepatocellular carcinoma. J Am Coll Surg 2015;220:297-304.e3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Azoulay D, Audureau E, Bhangui P, et al. Living or Brain-dead Donor Liver Transplantation for Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A Multicenter, Western, Intent-to-treat Cohort Study. Ann Surg 2017;266:1035-44. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Goldaracena N, Gorgen A, Doyle A, et al. Live donor liver transplantation for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma offers increased survival vs. deceased donation. J Hepatol 2019;70:666-73. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wong TCL, Ng KKC, Fung JYY, et al. Long-Term Survival Outcome Between Living Donor and Deceased Donor Liver Transplant for Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Intention-to-Treat and Propensity Score Matching Analyses. Ann Surg Oncol 2019;26:1454-62. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Liang W, Wu L, Ling X, et al. Living donor liver transplantation versus deceased donor liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma: a meta-analysis. Liver Transpl 2012;18:1226-36. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhu B, Wang J, Li H, et al. Living or deceased organ donors in liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. HPB (Oxford) 2019;21:133-47. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhang HM, Shi YX, Sun LY, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma recurrence in living and deceased donor liver transplantation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Chin Med J (Engl) 2019;132:1599-609. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Roberts JP, Venook A, Kerlan R, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma: Ablate and wait versus rapid transplantation. Liver Transpl 2010;16:925-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ince V, Ersan V, Karakas S, et al. Does Preoperative Transarterial Chemoembolization for Hepatocellular Carcinoma Increase the Incidence of Hepatic Artery Thrombosis After Living-Donor Liver Transplant? Exp Clin Transplant 2017;15:21-4. [PubMed]

- Cho CW, Choi GS, Kim JM, et al. Clinical usefulness of transarterial chemoembolization response prior to liver transplantation as predictor of optimal timing for living donor liver transplantation. Ann Surg Treat Res 2018;95:111-20. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kumar A, Acharya SK, Singh SP, et al. The Indian National Association for Study of the Liver (INASL) Consensus on Prevention, Diagnosis and Management of Hepatocellular Carcinoma in India: The Puri Recommendations. J Clin Exp Hepatol 2014;4:S3-S26. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sugawara Y, Tamura S, Makuuchi M. Living donor liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma: Tokyo University series. Dig Dis 2007;25:310-2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tamura S, Sugawara Y, Kokudo N. Section 4. Further expanding the criteria for HCC in living donor liver transplantation: the Tokyo University experience. Transplantation 2014;97:S17-20. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shimamura T, Akamatsu N, Fujiyoshi M, et al. Expanded living-donor liver transplantation criteria for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma based on the Japanese nationwide survey: the 5-5-500 rule - a retrospective study. Transpl Int 2019;32:356-68. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lee KW, Yi NJ, Suh KS. Section 5. Further expanding the criteria for HCC in living donor liver transplantation: when not to transplant: SNUH experience. Transplantation 2014;97:S20-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lee SD, Kim SH, Kim YK, et al. (18)F-FDG-PET/CT predicts early tumor recurrence in living donor liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma. Transpl Int 2013;26:50-60. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lee SD, Lee B, Kim SH, et al. Proposal of new expanded selection criteria using total tumor size and (18)F-fluorodeoxyglucose - positron emission tomography/computed tomography for living donor liver transplantation in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: The National Cancer Center Korea criteria. World J Transplant 2016;6:411-22. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lee KW, Suh SW, Choi Y, et al. Macrovascular invasion is not an absolute contraindication for living donor liver transplantation. Liver Transpl 2017;23:19-27. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Choi HJ, Kim DG, Na GH, et al. The clinical outcomes of patients with portal vein tumor thrombi after living donor liver transplantation. Liver Transpl 2017;23:1023-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lee HW, Song GW, Lee SG, et al. Patient Selection by Tumor Markers in Liver Transplantation for Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Liver Transpl 2018;24:1243-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Assalino M, Terraz S, Grat M, et al. Liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma after successful treatment of macrovascular invasion - a multi-center retrospective cohort study. Transpl Int 2020;33:567-75. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Navadgi S, Chang CC, Bartlett A, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of outcomes after liver resection in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) with and without bile duct thrombus. HPB (Oxford) 2016;18:312-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wang C, Yang Y, Sun D, et al. Prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma patients with bile duct tumor thrombus after hepatic resection or liver transplantation in Asian populations: A meta-analysis. PLoS One 2017;12:e0176827. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kim DS, Kim BW, Hatano E, et al. Surgical Outcomes of Hepatocellular Carcinoma With Bile Duct Tumor Thrombus: A Korea-Japan Multicenter Study. Ann Surg 2020;271:913-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kim JM, Kwon CH, Joh JW, et al. The effect of hepatocellular carcinoma bile duct tumor thrombi in liver transplantation. Hepatogastroenterology 2014;61:1673-6. [PubMed]

- Ha TY, Hwang S, Moon DB, et al. Long-term survival analysis of liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma with bile duct tumor thrombus. Transplant Proc 2014;46:774-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lee JH, Cho Y, Kim HY, et al. Serum Tumor Markers Provide Refined Prognostication in Selecting Liver Transplantation Candidate for Hepatocellular Carcinoma Patients Beyond the Milan Criteria. Ann Surg 2016;263:842-50. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Taketomi A, Sanefuji K, Soejima Y, et al. Impact of des-gamma-carboxy prothrombin and tumor size on the recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma after living donor liver transplantation. Transplantation 2009;87:531-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fujiki M, Takada Y, Ogura Y, et al. Significance of des-gamma-carboxy prothrombin in selection criteria for living donor liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma. Am J Transplant 2009;9:2362-71. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Han S, Yang JD, Sinn DH, et al. Risk of Post-transplant Hepatocellular Carcinoma Recurrence Is Higher in Recipients of Livers From Male Than Female Living Donors. Ann Surg 2018;268:1043-50. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Han S, Yang JD, Sinn DH, et al. Higher Bilirubin Levels of Healthy Living Liver Donors Are Associated With Lower Posttransplant Hepatocellular Carcinoma Recurrence. Transplantation 2016;100:1933-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Han S, Lee S, Yang JD, et al. Risk of posttransplant hepatocellular carcinoma recurrence is greater in recipients with higher platelet counts in living donor liver transplantation. Liver Transpl 2018;24:44-55. [Crossref] [PubMed]

马春阳

2017年06月毕业于华中科技大学同济医学院,获得外科学专业型硕士学位,2017年09月起至今,在南通市肿瘤医院肿瘤外科工作,主要从事腹部肿瘤的诊治工作。(更新时间:2021/9/19)

(本译文仅供学术交流,实际内容请以英文原文为准。)

Cite this article as: Leal-Leyte P, Zamora-Valdés D. Patient selection in liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma. Dig Med Res 2020;3:50.