炎症性肠病患者结直肠癌患病风险的综述

引言

溃疡性结肠炎(Ulcerative Colitis, UC)和克罗恩病(Crohn’s disease, CD)是炎症性肠病(Inflammatory bowel disease, IBD)的一部分,它们呈现慢性病程并且具有较高风险发展成为结直肠癌(colorectal cancer, CRC)。在世界范围内,这些并发症是癌症相关死亡最常见的诱因之一[1]。每10万人每年CD 和 UC 的发病:北美估计为 6.30-23.82 和 8.8-23.14,东欧为 0.40-14.6 和 0.97-11.9,南欧为 0.95-15.4 和 3.3-11.47,西欧为 1.85-10.5和1.9-17.2,东亚为0.06-3.2和0.42-4.6,西亚为0.94-8.4和0.77-6.5,大洋洲为12.96-29.3和7.33-11.4,非洲为5.87和3.29[2]。非洲裔美国人CRC发病率是7.9人/年,高于如非西班牙裔白人等其他种族,非西班牙裔白人CRC发病率是6.7人/年 [3]。非洲裔美国人与癌症相关的死亡风险为1.35(95% CI, 1.26–1.45),5 年生存率为 54.9%,比非西班牙裔白人的68.1%低 [4]。IBD患者演变为进展期CRC的危险因素包括:发病时间长、有散发CRC家族史、持续性结肠炎伴随原发性硬化性胆管炎(primary sclerosing cholangitis, PSC)[5]。多年来,CRC 和 UC 患者的死亡率有所下降,但 CD 的死亡率保持稳定,是普通人群死亡率的两倍 [6]。近期研究表明,由于内镜监测的频率增加和及时的诊断治疗,进展期 CRC 的发生率略有下降[7]。内镜监测旨在及时发现病变,降低早期死亡率,从而提高短期和长期存活率。 提高随访IBD患者的内镜医师的认识,使他们充分意识到随访监测的重要性,可以将 CRC 的发生频率降低至小于 5% [8,9]。本文的目的是归纳文献中关于 CRC 的证据、建议及其对 IBD 患者的影响。 本文根据 Narrative Review 报告清单进行综述(全文链接:http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/dmr-20-111)。

研究方法

通过在数据库 (PubMed) 中搜索具有以下关键字的论文来进行文献综述:“colorectal cancer”, “neoplasia”, “dysplasia”, “inflammatory bowel disease”, “ulcerative colitis”, “Crohn’s disease”, “epidemiology”, “treatment”, “endoscopy”, “guidelines”, “surveillance”。文献时间为2000年至2020年。

流行病学

IBD 患者 CRC 的流行病学研究集中在显示不同人群中CRC 的发生率和风险,并寻找与CRC进展相关的风险因素。匈牙利的研究者发现,在1974年至2004年期间,病程为10 年累积患病率为 0.6%,20 年累积患病率为 5.4%,30 年累积患病率为 7.5% [10]。一项meta分析显示,1972年至2004年期间,IBD患者患CRC的10 年累积风险为 2.9%, 20 年累积风险为 5.6%, 30 年累积风险为 8.3%。1970年至 2005年进行的一项韩国研究表明,病程10、20 和 30 年的IBD患者患CRC的累积风险分别为 0.7%、7.9% 和 33.2%。1969 年至 2017 年期间,在丹麦和瑞典进行的一项基于人群的队列研究发现UC 患者的发病率为1.29 人/千人/年,CRC 的发病率为0.82人/千人/年(95% CI,1.57–1.76),HR 1.66 [11]。一项大型单中心回顾性研究纳入了 166 例 PSC 患者,进行了平均10年的随访,其中 120 例诊断为 UC,35 例诊断为CD,11 例诊断为不确定性结肠炎。 在所有纳入的患者中,只有 1 名 CD 患者发展为异型增生。对纳入的 UC 患者进行了平均时间为 11 年的随访,发现2 例CRC和 8 例异型增生[12]。在欧洲进行的一项为期 15 年的随访研究中,681 名患者中有 9 名 (1.3%) 检测到 CRC,其中 1 名诊断为 CD,8 名诊断为 UC [13]。在一项包含2,621 名 IBD 患者的中国研究发现13 名 UC 和 6 名 CD 患者并发 CRC [14]。在对美国退伍军人的研究中,IBD 患者的发病率为 148/100,000,对照组为 97/100,000; RR:1.53(95% CI,0.86–2.69) [15]。在 IBD 确诊后的初始十年中,CRC 的总体风险为每 1,000 人年 0.91,而在第二个十年中为每 1,000 人年 4.07 [16]。在 IBD 和 PSC 患者中,从疾病发作起 20 年内发生 CRC 的风险约为 30% [17]。从 IBD 症状开始就进行内镜的随访监测非常重要。有研究显示 确诊CRC时 UC 持续的中位时间为 16 年(0-64 年),确诊CRC的中位年龄介于 46 岁(17-85 岁)和 23.5 岁(11-48 岁)之间 [10]。IBD患者并发CRC的性别差异目前尚不明确。但一些研究发现,这种情况在男性中更常见,男性患结肠癌的风险高于女性 3.2 vs 2.2,来自美国的两项研究发现,没有IBD的CRC患者超过一半是男性[18]。在正常人群中,小肠腺癌很少见;而对于IBD 患者,尤其是 CD 患者,小肠腺癌的风险是非 CD 患者的两倍,并且风险随着疾病时间的延长而增加。 CD 病灶进展成为小肠腺癌多由影像学检查发现,在极少数情况下是在进行与其症状无关的外科手术过程中偶然发现或自发性穿孔等 [19]。

病因

散发性 CRC通常有一个特定的过程,其中第一个变化是腺瘤的形成,从不典型增生开始、逐步进展成为低度不典型增生、高度不典型增生和癌,而在与 IBD 相关的 CRC 中,并不遵循这个特定的过程。IBD相关的CRC发生和发展的过程可能十分短暂。导致 IBD 患者罹患肿瘤的因素包括慢性炎症过程及其免疫反应、遗传改变、微生物群改变、疾病持续时间、疾病严重程度、合并PSC、发病年龄较年轻、解剖学异常、CRC 家族史 [20]。

促炎症性细胞因子

许多细胞因子、趋化因子和环氧化酶 (COX)-2 的诱导是 IBD 炎症的原因,这些因子促进细胞迁移,并且随着时间的推移,其可能促进肿瘤的形成 [21]。有证据表明,非甾体抗炎药通过抑制细胞因子对 COX 酶的作用,可降低50%普通人群患CRC的风险[22]。

遗传

先前在动物模型中的研究发现,CRC的发生是由胃肠道中长期的炎症过程引起的,IBD患者的特点是具有持续的炎症过程,导致胃肠道粘膜细胞的高水平氧化应激,并伴有持续的DNA损伤和癌基因的激活 [23]。在疾病的演变过程中,基因突变不断累积,导致癌基因如致癌基因 K-ras激活,抑癌基因 APC、p53 和 MYC 的失活 [24]。这些基因突变在普通CRC 患者中同样存在,不同之处在于它们在 IBD 患者中发生的更早 [25]。遗传改变的特征在于三个过程:(I)染色体不稳定性 (CIN),这是散发性 CRC 中最常见的,其特征在于非整倍体保留修复机制。(II)特定 DNA 序列的插入和缺失导致的微卫星不稳定性 (MSI)。(III)CpG岛甲基化:这发生在少数肿瘤中,并且预示着预后不良[26]。

危险因素

对于散发性 CRC,危险因素主要是不良的生活方式,如肥胖、缺少体力活动、酒精、吸烟和高脂肪饮食,但尚未发现这些因素与IBD 患者罹患CRC之间相关,IBD患者发生CRC最重要的危险因素似乎均与炎症过程相关,如合并PSC、疾病严重程度、疾病持续时间、组织学活动、狭窄、假性息肉和既往发现不典型增生,没有这些危险因素的患者很少发生 CRC [25]。

患者相关的CRC危险因素

高龄

无论是 IBD 患者还是非 IBD 患者,老年人患 CRC 的风险均增加。发病率增加发生在 60 岁和 70 岁之间,老年病人需要手术和出现并发症的风险也更高 [27]。近年来,50 岁以下患者的 CRC 病例迅速增加,其中约 11% 的 CRC 位于该年龄组 [28]。在 IBD 患者中,由于患者出现的慢性炎症过程,肿瘤的发生通常在年轻时出现。

CRC家族史

结肠和直肠发生恶性病变具有遗传倾向,因此CRC家族史是普通人群CRC发病的一个重要因素。多达 10% 的 CRC 患者至少有一个一级亲属患过相同类型的癌症,当家庭成员在 50 岁以下时患癌,则亲属患病风险会更大。然而IBD患者与普通人群不同, CRC家族史与 IBD 患者无关 [29]。

CRC菌群

菌群的变化与多种类型的疾病有关,其中一个例子是幽门螺杆菌与胃癌相关。 在癌组织中,黏膜中细菌的多样性较低,以普通拟杆菌、长双歧杆菌、瘤胃球菌、白色瘤胃球菌、汉森链球菌、普氏杆菌为主,这些细菌与CRC 的风险增加有关 [6]。所有这些已被全基因组测序证实,并与MSI有关[30]。同时,一些细菌如鼠李糖乳杆菌、消化链球菌、罗氏菌、乳双歧杆菌抑制CRC的发生也被全基因组测序证实[31]。有几种理论,主要的一种是driver-passenger理论:如果优势细菌是促癌的,其可招募其他细菌群,引起组织重塑,共同促进 CRC[32]。

IBD相关的CRC发生危险因素

IBD的持续时间

最常见的相关风险因素是发病时间[25]。重要的是明确确诊时间,以便立即开始CRC 的监测计划。开始监测的时间可能因每位患者的风险因素而异。病程越长,黏膜炎症越重,发展为 CRC 和其他肿瘤的风险也就越高。

疾病严重程度

全结肠炎患者患CRC 风险最高,左侧结肠炎和直肠炎风险较低。但是最近的一项研究表明,全结肠炎是唯一风险 [11],受炎症影响的区域越大,IBD 的炎性细胞数就越多。尽管患有广泛的结肠炎,但如果患者在疾病过程中出现几次复发,CRC风险可能会降低[33]。对于IBD频繁复发和长期持续的患者,镜下炎症表现是发生 CRC 的独立危险因素。 对于UC 患者,组织学缓解可降低 CRC 的发病风险。因此仅仅达到内镜缓解并不够[34]。组织学缓解已被提出作为治疗IBD的目标,有必要将概念和量表标准化以供普遍使用,这将是未来几年的目标[35]。

PSC

大多数 PSC 患者患有 IBD [36],估计 PSC 患者的 IBD 患病率高达 50% [37]。UC的肠外表现以胆汁酸过多为特征,在PSC患者中,由于胆汁酸影响细胞增殖而成为主要发病机制。这些患者属于发生结直肠癌的高危类别,发病时间较短且预后较差。恶性肿瘤约占PSC患者死亡率的40%~50% [38]。 这些患者具有一些特点:患有 UC、重型全结肠炎、右半结肠癌症的概率增加 [39]、IBD 诊断和症状出现的年龄较小、预后较差,5 年生存率为 40% [40]。

IBD早期发病

在IBD患者中,IBD早期发病是CRC的主要危险因素。这些患者往往具有更长的活动期、更具侵袭性的临床模式并在早期出现并发症。与在平均年龄诊断的患者中发生的情况相反,后者可能临床症状轻微,结肠炎症期短 [41]。

解剖异常

假性息肉在炎症过程中形成,浸润粘膜和粘膜下层,在这些区域形成肉芽组织,以淋巴细胞、浆细胞、中性粒细胞和嗜酸性粒细胞为特征,在炎症愈合后形成息肉。研究表明,3.5%的狭窄会发展为癌前病变,并且它们转化为 CRC 的比率最高。 正如假性息肉在炎症过程中形成一样,狭窄可以反映疾病活动以及病变的侵袭性[42]。

反流性回肠炎

反流性回肠炎是指结肠内容物反流入回肠末端,引起回肠末端炎症。多达三分之一的UC 患者患有反流性回肠炎 [43]。反流性回肠炎已被提议作为该区域发生肿瘤的危险因素。先前的一项研究表明,反流性回肠炎与肿瘤形成有关,这可能是因为大多数具有此特征的患者同时患有其他许多疾病,这些疾病同样是CRC的危险因素。

预防性化学药物治疗

减少肠道炎症是治疗IBD的基石,这些治疗可以通过减少炎症和复发来降低CRC的发生率。IBD的治疗药物如5-氨基水杨酸盐 (5-ASA)、硫唑嘌呤和生物制剂可能是潜在的预防CRC的方法。在分子研究中唯一被认为具有预防CRC作用的药物是 5-ASA, 每天口服大于1.2 克的 5-ASA 可降低 IBD 患者的 CRC 风险[44]。胆汁酸是恶性肿瘤发展的重要原因,用熊去氧胆酸治疗可减少胆汁酸的分泌,能够降低合并PSC 的 IBD 患者患 CRC 的风险。 然而,熊去氧胆酸的化学保护作用尚未深入研究,也不被广泛推荐作为一般人群或IBD患者的预防CRC的治疗手段。

诊断和监测策略

对于结肠受累的IBD患者,结肠镜监测可以早期发现异型增生和早期CRC。在IBD患者中,一次内镜监测的益处估计长达5年,这是普通人群的 10 倍。异型性增生的诊断是一项挑战,因为在大多数情况下,患者无任何症状,其检测可能取决于操作者的经验,以及内窥镜医师的能力和专业知识。在大多数情况下,无论操作者的能力如何,如果患者在检查时处于IBD活动期,则可能难以检测到异常增生[3]。因此,结肠镜筛查建议在临床缓解期进行,这样不仅可以看到黏膜的炎症变化同时也可检测异常增生。结肠镜监测的间隔时间应根据CRC 危险因素和结肠镜检查的既往结果来决定 [45]。训练有素的内窥镜操作者、完善的肠道准备、高清内镜设备以及使用染色内镜等提高病变检测的技术、检查持续时间较长均能够提高异型增生或CRC病变的检出率。同时,多点结肠组织活检也可增加异型增生的检出率[46]。

与随机活检相比,使用染色内镜进行靶向活检是一种更实用经济的技术,其不仅具有传统结肠镜检查的优点,并且能够更加精准的发现异型增生[47]。有研究已经证明,使用靶向活检,异型增生病变的检出率更高,约为11.4%,而随机活检仅为9.3% [47]。最近的一项荟萃分析比较了标准白光内窥镜和高清白光内窥镜的检查功效,尚无法证明高清白光内镜的检出率优于标准白光内镜,唯一被证实的是染色内镜检出率优于标准白光内窥镜[48]。影像学、内镜学和组织学的多项研究结果表明,随着时间的推移,全结肠炎与更高的癌症风险有关 [49]。已经证明,染色内镜联合白光内镜比其他结肠镜技术具有更高的结肠病变检出率,并且检测异性增生所需的活检数量减少了一半。这种联合检查方法与CRC相关的死亡率的显着降低有关,因此现在被许多学会视为标准诊治方法 [50]。当对异型增生进行活检时,应由专门研究胃肠道病变的病理学家对其进行病理评估 [51]。

风险分层

IBD患者通常根据患CRC的风险进行分类,分为高危组、中危组和低危组[52]。高危组:患有PSC、内镜或组织学炎症活动活跃、既往发现异型增生、一级CRC家族史的患者。 中危组:两次结肠镜检查阴性,内镜或组织学炎症活动中等,存在炎性息肉。其他为低危组。在没有任何风险的人群中,一般建议是从确诊IBD起平均8-10年开始监测 [5,46,49,51-53]。不同的学会对监测提出了不同的建议,如表1所示。

Full table

储袋肿瘤

接受结直肠切除术和回肠储袋肛门吻合术 (IPAA) 的患者既往有异常增生或癌症、PSC和持续性萎缩以及难治性储袋炎时,发生储袋瘤的风险更高 [45]。据报道,IPAA 患者的储袋瘤形成在20年间的发生率为4.2%~6.9% [54-56]。由于存在排便方式的改变,IPAA 患者很少被怀疑有肿瘤形成,一些指南建议对具有CRC和难治性储袋炎病史的高危人群进行年度监测 [5,46,53]。低风险患者每5年一次 [46]。对于没有风险因素的其他人群,进行密切监测的证据尚不足 [5,51]。

内镜和手术治疗

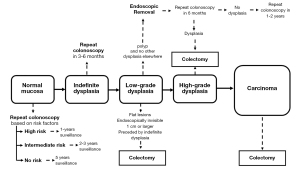

根据不典型增生的程度,可以使用各种治疗策略。重要的是要了解病变的类型,这些病变类型包括“平坦”型(不易发现的病变)和“隆起”型(易发现到的病变)[57]。治疗策略如图1所示。

内镜切除术

发现异型增生后,无论异型增生的程度如何,都需要由经验丰富的内镜医师在内镜下完全切除[53]。患者异型增生息肉样病变完全切除后还应进行密切的内镜监测,应在6个月进行复查,检测复发或新的病灶[58]。对于低级别瘤变的患者,多发性病灶是结肠切除的指征[59],而对于低级别的单发病灶则采取保守的治疗措施[45,53]。当发现与低度异型增生相对应的特征时,病理学家会给出不确定的异型的诊断。除此之外,活跃的炎症常常使其无法区分结构的变化是由于低度异型增生还是炎症过程本身引起的。大约18%~28%的异常增生进展为晚期肿瘤 [57]。指南建议在3至12个月内进行结肠镜复查,复查最好使用色素内镜进行[45,57]。

结肠切除术

如果多灶性LGD或HGD无法进行内镜下切除,则应考虑外科手术治疗[46],因为这类病变发生CRC 的风险很高。由于恶性肿瘤的浸润风险高于40%,因此在癌变和高度异型增生的情况下需要进行结肠切除术。对于狭窄的患者,或有先前通过内镜切除损伤病史的患者,也应考虑进行结肠切除术。之前的一项荟萃分析表明,在内镜下切除息肉样异型增生后,发生 CRC的风险降低,但异型增生的风险仍然持续存在,这就是为什么一些学会建议对此类病变进行结肠切除术的原因。内镜下无可见病变的CD发生腺癌或高度异型增生是结肠切除的手术指征[45]。 大约40%的部分切除或次全结肠切除的CD患者可能患有异时性癌症,死亡率很高[60]。

预后

生存期取决于发现的病灶分期,如果及时发现并采用内镜切除治疗,5年生存率可达98%以上,结直肠切除术对于早期病变的生存率相同。有恶性病变史的高危组患者,每年应进行密切随访。 IBD 患者CRC的复发率可能高达 35% [61]。

CRC和IBD的研究展望

微生物群在CRC的发展中起着重要作用。近年来,筛查致癌肠道微生物群作为诊断CRC的标记物取得了可喜的结果,有望成为一种侵入性较小的诊断辅助工具 [62-65]。除了微生物群标记物,血液和粪便样本中的肿瘤标志物,例如miRNA、肿瘤相关抗原、丙酮酸激酶的肿瘤特异性M2异构体、基质金属蛋白酶抑制剂1也被用作临床辅助诊断。这些标记物是由肿瘤产生的分子,灵敏度大于90% [66]。近年来,新的内镜技术不断发展。共聚焦激光内窥镜(CLE)是一种新技术,可以在内镜观察胃肠粘膜时进行细胞实时可视化。使用这项新技术,可以实时获得有关微观结构的详细信息,从而能够发现微观炎症和异型增生的存在 [67]。对CRC进行传统化疗,会引发这些患者的病情恶化和IBD活动。寻找新疗法,例如有机金属化合物和金属配合物十分必要,因为它们同时具有抗炎作用 [68]。

总结

IBD患者发生CRC的概率非常低。与异型增生和CRC发展相关的风险因素包括:疾病严重程度、疾病持续时间、PSC和持续性黏膜炎症。监测应根据危险因素进行分层,高危组:合并PSC、内镜或组织学炎性活动活跃、既往不典型增生、一级CRC家族史;中危组:两次结肠镜检查阴性,内镜或组织学活动中等,存在炎症后息肉。欧洲克罗恩病和结肠炎组织 (ECCO)和美国胃肠病学会(ACG)指南相似,只是在风险分层方面,ECCO考虑了三个不同的风险组(高、中和低),而ACG仅将其分为高风险组和低风险组。

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Provenance and Peer Review: This article was commissioned by the Guest Editor (Nahum Méndez-Sánchez) for the series “Current Status and Future Expectations in the Management of Gastrointestinal Cancer” published in Digestive Medicine Research. The article has undergone external peer review.

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the Narrative Review reporting checklist. Available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/dmr-20-111

Peer Review File: Available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/dmr-20-111

Conflicts of Interest: Both authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/dmr-20-111). The series “Current Status and Future Expectations in the Management of Gastrointestinal Cancer” was commissioned by the editorial office without any funding or sponsorship. The authors have no other conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Ferlay J, Colombet M, Soerjomataram I, et al. Estimating the global cancer incidence and mortality in 2018 : GLOBOCAN sources and methods. Int J Cancer 2019;144:1941-53. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ng SC, Shi HY, Hamidi N, et al. Worldwide incidence and prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease in the 21st century: a systematic review of population-based studies. Lancet 2018;390:2769-78. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dulai PS, Sandborn WJ, Gupta S. Colorectal cancer and dysplasia in inflammatory bowel disease: a review of disease epidemiology, pathophysiology, and management. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2016;9:887-94. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Holowatyj AN, Ruterbusch JJ, Rozek LS, et al. Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Survival Among Patients With Young-Onset Colorectal Cancer. J Clin Oncol 2016;34:2148-56. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Annese V, Beaugerie L, Egan L, et al. European Evidence-based Consensus : Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Malignancies. J Crohns Colitis 2015;9:945-65. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Song M, Chan AT. Environmental Factors, Gut Microbiota, and Colorectal Cancer Prevention. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2019;17:275-89. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Keller DS, Windsor A, Cohen R, et al. Colorectal cancer in inflammatory bowel disease : review of the evidence. Tech Coloproctol 2019;23:3-13. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Singh K, Al Khoury A, Kurti Z, et al. High Adherence to Surveillance Guidelines in Inflammatory Bowel Disease Patients Results in Low Colorectal Cancer and Dysplasia Rates, While Rates of Dysplasia are Low Before the Suggested Onset of Surveillance. J Crohns Colitis 2019;13:1343-50. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Burke KE, Nayor J, Campbell EJ, et al. Interval Colorectal Cancer in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: The Role of Guideline Adherence. Dig Dis Sci 2020;65:111-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhiqin W, Palaniappan S, Raja Ali RA. Inflammatory Bowel Disease-related Colorectal Cancer in the Asia-Pacific Region: Past, Present, and Future. Intest Res 2014;12:194-204. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Olén O, Erichsen R, Sachs MC, et al. Colorectal cancer in ulcerative colitis: a Scandinavian population-based cohort study. Lancet 2020;395:123-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Palmela C, Peerani F, Castaneda D, et al. Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis: A Review of the Phenotype and Associated Specific Features. Gut Liver 2018;12:17-29. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhou Q, Shen ZF, Wu BS, et al. Risk of Colorectal Cancer in Ulcerative Colitis Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Gastroenterol Res Pract 2019;2019:5363261. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- So J, Tang W, Leung WK, et al. Cancer Risk in 2621 Chinese Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Population-based Cohort Study. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2017;23:2061-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mosher CA, Brown GR, Weideman RA, et al. Incidence of Colorectal Cancer and Extracolonic Cancers in Veteran Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2018;24:617-23. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Castaño-Milla C, Chaparro M, Gisbert JP. Systematic review with meta-analysis: the declining risk of colorectal cancer in ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2014;39:645-59. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wang R, Leong RW. Primary sclerosing cholangitis as an independent risk factor for colorectal cancer in the context of inflammatory bowel disease: A review of the literature. World J Gastroenterol 2014;20:8783-9. [PubMed]

- Kim SE, Paik HY, Yoon H, et al. Sex- and gender-specific disparities in colorectal cancer risk. World J Gastroenterol 2015;21:5167-75. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bojesen RD, Riis LB, Høgdall E, et al. Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Small Bowel Cancer Risk, Clinical Characteristics, and Histopathology: A Population-Based Study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017;15:1900-7.e2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fumery M, Dulai PS, Gupta S, et al. Incidence, Risk Factors, and Outcomes of Colorectal Cancer in Patients With Ulcerative Colitis With Low-Grade Dysplasia: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017;15:665-74.e5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lasry A, Zinger A, Ben-Neriah Y. Inflammatory networks underlying colorectal cancer. Nat Immunol 2016;17:230-40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yao D, Dong M, Dai C, et al. Inflammation and Inflammatory Cytokine Contribute to the Initiation and Development of Ulcerative Colitis and Its Associated Cancer. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2019;25:1595-602. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Beaugerie L, Itzkowitz SH. Cancers. Cancers Complicating Inflammatory Bowel Disease. N Engl J Med 2015;372:1441-52. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Robles AI, Traverso G, Zhang M, et al. Whole-Exome Sequencing Analyses of Inflammatory Bowel Disease-Associated Colorectal Cancers. Gastroenterology 2016;150:931-43. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kim ER, Chang DK. Colorectal cancer in inflammatory bowel disease: The risk, pathogenesis prevention and diagnosis. World J Gastroenterol 2014;20:9872-81. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Salama RH, Sayed ZEA, Ashmawy AM, et al. Interrelations of Apoptotic and Cellular Senescence Genes Methylation in Inflammatory Bowel Disease Subtypes and Colorectal Carcinoma in Egyptians Patients. Appl Biochem Biotechnol 2019;189:330-43. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jafari MD, Jafari F, Halabi WJ, et al. Colorectal Cancer Resections in the Aging US Population A Trend Toward Decreasing Rates and Improved Outcomes. JAMA Surg 2014;149:557-64. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fedewa SA, et al. Colorectal Cancer Statistics, 2017. CA Cancer J Clin 2017;67:177-93. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Henrikson NB, Webber EM, Goddard KA, et al. Family history and the natural history of colorectal cancer: systematic review. Genet Med 2015;17:702-12. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wong SH, Yu J. Gut microbiota in colorectal cancer: mechanisms of action and clinical applications. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2019;16:690-704. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lucas C, Barnich N, Nguyen HTT. Microbiota, Inflammation and Colorectal Cancer. Int J Mol Sci 2017;18:1310. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gao R, Gao Z, Huang L, et al. Gut microbiota and colorectal cancer. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2017;36:757-69. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Li J, Zhou WX, Liu S, et al. Similarities and differences in clinical and pathologic features of inflammatory bowel disease-associated colorectal cancer in China and Canada. Chin Med J (Engl) 2019;132:2664-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Negreanu L, Voiosu T, State M, et al. Endoscopy in inflammatory bowel disease: from guidelines to real life. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2019;12:1756284819865153. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bryant RV, Winer S, Travis SP, et al. Systematic review: Histological remission in inflammatory bowel disease. Is ‘complete’ remission the new treatment paradigm? An IOIBD initiative. J Crohns Colitis 2014;8:1582-97. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tsaitas C, Semertzidou A, Sinakos E. Update on inflammatory bowel disease in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis. World J Hepatol 2014;6:178-87. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- de Vries AB, Janse M, Blokzijl H, et al. Distinctive inflammatory bowel disease phenotype in primary sclerosing cholangitis. World J Gastroenterol 2015;21:1956-71. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Folseraas T, Boberg KM. Cancer Risk and Surveillance in Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis. Clin Liver Dis 2016;20:79-98. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zheng HH, Jiang XL. Increased risk of colorectal neoplasia in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis and inflammatory bowel disease: a meta-analysis of 16 observational studies. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2016;28:383-90. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ricciuto A, Kamath BM, Griffiths AM. The IBD and PSC Phenotypes of PSC-IBD. Curr Gastroenterol Rep 2018;20:16. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Crowley E, Muise A. Inflammatory Bowel Disease: What Very Early Onset Disease Teaches Us. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 2018;47:755-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fumery M, Pineton de Chambrun G, Stefanescu C, et al. Detection of Dysplasia or Cancer in 3.5% of Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Colonic Strictures. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015;13:1770-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Patil DT, Odze RD. Backwash Is Hogwash: The Clinical Signifi cance of Ileitis in Ulcerative ColitisDeepa T. Patil M 1, and Robert D. Odze M. Backwash Is Hogwash: The Clinical Signifi cance of Ileitis in Ulcerative Colitis. Am J Gastroenterol 2017;112:1211-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bonovas S, Fiorino G, Lytras T, et al. Systematic review with meta-analysis: use of 5-aminosalicylates and risk of colorectal neoplasia in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2017;45:1179-92. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Annese V, Daperno M, Rutter MD, et al. European evidence based consensus for endoscopy in inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis 2013;7:982-1018. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cairns SR, Scholefield JH, Steele RJ, et al. Guidelines for colorectal cancer screening and surveillance in moderate and high risk groups (update from 2002). Gut 2010;59:666-89. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Watanabe T, Ajioka Y, Mitsuyama K, et al. Comparison of Targeted vs Random Biopsies for Surveillance of Ulcerative Colitisassociated Colorectal Cancer. Gastroenterology 2016;151:1122-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Feuerstein JD, Rakowsky S, Sattler L, et al. Meta-analysis of dye-based chromoendoscopy compared with standard- and high-definition white-light endoscopy in patients with inflammatory bowel disease at increased risk of colon cancer. Gastrointest Endosc 2019;90:186-95.e1. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rubin DT, Ananthakrishnan AN, Siegel CA, et al. ACG Clinical Guideline: Ulcerative Colitis in Adults. Am J Gastroenterol 2019;114:384-413. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ananthakrishnan AN, Cagan A, Cai T, et al. Colonoscopy Is Associated With a Reduced Risk for Colon Bowel Diseases. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015;13:322-9.e1. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Farraye FA, Odze RD, Eaden J, et al. AGA Medical Position Statement on the Diagnosis and Management of Colorectal Neoplasia in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Gastroenterology 2010;138:738-45. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yamamoto-Furusho JK, Bosques-Padilla F, Daffra P, et al. Special situations in inflammatory bowel disease: First Latin American consensus of the Pan American Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation (PANCCO) (Second part). Rev Gastroenterol Mex 2017;82:134-55. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy Standards of Practice Committee. The role of endoscopy in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastrointest Endosc 2015;81:1101-21.e213. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mark-Christensen A, Erichsen R, Brandsborg S, et al. Long-term Risk of Cancer Following Ileal Pouch-anal Anastomosis for Ulcerative Colitis. J Crohns Colitis 2018;12:57-62. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Khan F, Shen B. Inflammation and Neoplasia of the Pouch in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Curr Gastroenterol Rep 2019;21:10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gonzalo DH, Collinswortha AL, Liua X. Common Inflammatory Disorders and Neoplasia of the Ileal Pouch: A Review of Histopathology. Gastroenterology Res 2016;9:29-38. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Farraye FA, Odze RD, Eaden J, et al. AGA Technical Review on the Diagnosis and Management of Colorectal Neoplasia in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Gastroenterology 2010;138:746-74. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pulusu SSR, Lawrance IC. Surveillance in inflammatory bowel disease. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017;11:711-22. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Verschuren EC, Ong DE, Kamm MA, et al. Inflammatory bowel disease cancer surveillance in a tertiary referral hospital: attitudes and practice. Intern Med J 2014;44:40-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wanders LK, Dekker E, Pullens B, et al. Cancer Risk After Resection of Polypoid Dysplasia in Patients With Longstanding Ulcerative Colitis: A Meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014;12:756-64. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dugum M, Lin J, Lopez R, et al. Recurrence and survival rates of inflammatory bowel disease-associated colorectal cancer following postoperative chemotherapy: a comparative study. Gastroenterol Rep (Oxf) 2017;5:57-61. [PubMed]

- Yu J, Feng Q, Wong SH, et al. Metagenomic analysis of faecal microbiome as a tool towards targeted non-invasive biomarkers for colorectal cancer. Gut 2017;66:70-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Xie YH, Gao QY, Cai GX, et al. Fecal Clostridium symbiosum for Noninvasive Detection of Early and Advanced Colorectal Cancer: Test and Validation Studies. EBioMedicine 2017;25:32-40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Liang Q, Chiu J, Chen Y, et al. Fecal Bacteria Act as Novel Biomarkers for Non-Invasive Diagnosis of Colorectal Cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2017;23:2061-70. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Thomas AM, Manghi P, Asnicar F, et al. Metagenomic analysis of colorectal cancer datasets identifies cross-cohort microbial diagnostic signatures and a link with choline degradation. Nat Med 2019;25:667-78. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lech G, Słotwiński R, Słodkowski M, et al. Colorectal cancer tumour markers and biomarkers: Recent therapeutic advances. World J Gastroenterol 2016;22:1745-55. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Buchner AM. Confocal Laser Endomicroscopy in the Evaluation of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2019;25:1302-12. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Szczepaniak A, Fichna J. Organometallic Compounds and Metal Complexes in Current and Future Treatments of Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Colorectal Cancer-a Critical Review. Biomolecules 2019;9:398. [Crossref] [PubMed]

李杨

医学博士在读,南京中医药大学附属医院(江苏省中医院)消化内镜中心主治医师,主要从事消化系统肿瘤的临床和基础研究,近五年共发表论文20余篇,其中以第一作者发表SCI 5篇。(更新时间:2021/9/2)

冯雯卿

医学博士,上海交通大学医学院附属瑞金医院普外科博士后,毕业于上海交通大学医学院临床医学八年制专业, 2020年至今工作于上海交通大学医学院附属瑞金医院普外科博士后工作站,从事结直肠肿瘤以及肿瘤免疫微环境相关研究。(更新时间:2021/9/2)

(本译文仅供学术交流,实际内容请以英文原文为准。)

Cite this article as: Yamamoto-Furusho JK, Parra-Holguín NN. Narrative review of colorectal cancer risk in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Med Res 2020;3:56.