T4期结肠癌的治疗现状及治疗中的争议--文献叙述性综述

前言

结直肠癌是世界上第三大常见的恶性肿瘤,约10%的局部晚期(LACC)患者在确诊时有腹膜受累(T4a)或邻近器官受累(T4b)[1,2],无论男性或者女性均占肿瘤相关死亡的第三位[3]。结肠癌患者的预后在很大程度上与他们的TNM分期有关,所有T4期肿瘤的5年疾病特异性生存率为75%[4],然而,在这当中T4a肿瘤的5年生存率明显高于T4b肿瘤(61% vs. 46%)[5,6],强调了术前分期的重要性。通过利用新辅助化疗(NAC)和(或)新辅助放疗(NRT)来增加其实现R0切除的机会,目前仍然存在一些争议。

我们通过以下文章完成文献叙述性综述(可在https://dmr.amegroups.com/article/view/6413/rc 查阅相关文章)。

方法

利用MEDLINE(通过PubMed)和EMBASE(通过OvidSP)数据库对该领域的所有英文文章进行文献检索。通过临床试验注册表(https://clinicaltrials.gov)确定了正在进行的研究。研究包括:前瞻性随机对照试验、前瞻性非随机试验、回顾性研究、病例报告、综述、荟萃分析和会议摘要都包括在内。此外,还进行了相关文章的人工检索。使用的关键词包括"局部晚期结肠癌"、"高危T3"和"T4结肠癌"中的"新辅助化疗"、"新辅助放化疗"、"新辅助放疗"。发生转移的局部晚期结肠癌(LACC)相关研究被排除。

术前检查

欧洲医学肿瘤学协会(ESMO)和美国国立综合癌症网络(NCCN)的术前工作指南包含血液的基线检测,包括癌胚抗原(CEA),可能的话术前要进行结肠镜检查,但是在紧急情况下可以在术后进行,以及胸部、腹部和盆腔的计算机断层扫描(CT)[7]。在CT表现不明确或有静脉注射造影剂过敏的情况下,NCCN推荐正电子发射断层扫描(PET)以提供进一步的说明[8]。

临床上,由于T4期肿瘤是局部晚期的,在急诊手术中诊断的肿瘤高达69%,而择期手术组则为26%[9]。在肿瘤穿孔引起肠梗阻或腹膜炎的情况下,术前CT扫描可以充分描述病变,但无法准确辨别肿瘤的局部侵袭程度或是否有淋巴结受累。

在择期手术的病例中,Nerad等人最近的一项荟萃分析[10]发现CT分期对约1/3的患者过高,在检测肿瘤侵犯肠壁的敏感性为90%,但特异性为69%。迄今为止,没有研究能够解释低特异性的原因,然而,建议放射科医生将良性促结缔组织增生反应引起的微小肠系膜脂肪堆积解释为肿瘤侵袭,以最大限度地降低分期不足的风险。这是结直肠分期中公认的问题[11]。

腹部CT在检测远处转移方面是非常重要的,特别是在T4期结肠癌中有很高的远处转移的风险(高达45%的病例),以及淋巴结受累的风险(高达65%的病例)[12,13]。

磁共振成像(MRI)在直肠癌的术前分期中已得到认可[14],因为它比CT具有更好的软组织对比度,可以对肠壁各层及其邻近结构进行更高分辨率的成像。许多研究对MRI和CT对LACC的诊断性能进行了比较,MRI在定义是否有浆膜受累的T3肿瘤和T4肿瘤方面有优势,因为与CT相比,它有较高的特异性和较低的假阳性[15-19],可以减少过度分期。再加上其在检测肝转移和壁外血管侵犯(EMVI)方面的精确性,MRI可以被认为是高危结肠癌患者的最佳腹部分期方法[18]。

分子检测,特别是微卫星不稳定性(MSI)、BRAF和KRAS突变,目前是局部晚期和(或)转移性结肠癌患者的常规检测,因为它不仅有助于预测预后,而且还有助于指导治疗[8]。MSI是一种由于DNA错配修复(MMR)机制缺陷导致的一种遗传不稳定性。有MSI的人比微卫星稳定(MSS)的人预后更好,尤其重要的是15%~20%的II期和III期结肠癌患者是MMR缺陷或MSI[20]。迄今为止,BRAF突变在指导治疗决策方面没有明确的作用,但是在预测预后方面是有用的,虽然已经证明BRAF突变的转移性结肠癌患者的生存率明显较低[21],但是它在非转移性LACCs中的预后作用仍有争议,特别是在MSI与MSS肿瘤中[22]。靶向治疗通常与化疗一起进行,主要由肿瘤的KRAS突变状态来指导。KRAS突变预示着对表皮生长因子受体(EGFR)抑制剂,如西妥昔单抗和帕尼单抗的耐药性,因此它们只限于用于KRAS野生型肿瘤的患者[23],其他靶向单克隆抗体包括贝伐单抗【抗血管内皮生长因子(VEGF)】和雷莫芦单抗【抗血管内皮生长因子受体(VEGFR)】 [24]。

术前分期的重要性在于回答一个主要问题—患者是否有可能接受扩大的R0切除术?

治疗策略

在择期手术的情况下,NCCN根据有无梗阻症状,概述了对可切除结肠癌的处理。非梗阻性结肠癌的手术方法是结肠切除和区域淋巴结清扫,而对于梗阻性结肠癌,建议在结肠切除术时或术前行临时改流[8]。重要的是,在不可能或难以实现根治性切除的紧急情况下,例如出现肠梗阻但没有肿瘤穿孔或腹膜炎的患者,应考虑切除原发灶,这不仅有利于减轻荷瘤,还有利于新辅助治疗。

局部晚期结肠癌的新辅助化疗

肿瘤完整切除后的辅助性化疗(AC)是目前LACC患者的标准治疗方法,然而这可能需要广泛的多脏器切除以获得镜下切缘阴性[25]。尽管采用了这种积极的手术方式,但R0切除率仍然偏低,在40%~90%之间[25,26],术后发病率和死亡率也随之增加[26]。

新辅助化疗(NAC)被认为可以促进肿瘤的退缩,旨在降低肿瘤的分期[27],增加可切除性并促进更高的局部控制率,从而实现更多的R0切除[28-31]。这已被证明对局部晚期食道癌[32]、胃癌[33]、直肠癌[34]和乳腺癌[35]有效。

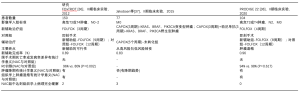

然而,到目前为止,对LACC的NAC研究还很少;主要基于几个II期试验的新数据[36,37],NCCN增加了NAC作为临床T4b疾病患者的治疗选择[8]。表1总结了所有已发表LACC的NAC的随机对照试验的研究。

Full table

FOxTROT协作组[36]调查了LACC术前化疗的可行性、安全性和有效性。在这项随机对照试验中,来自英国多个中心的150名放射学分期为局部晚期高危T3(侵入固有肌层≥5毫米)或T4肿瘤患者被随机分配到3个周期的新辅助FOLFOX(亚叶酸、氟尿嘧啶和奥沙利铂),然后进行手术,随后进行9个周期的辅助治疗,或者预先行肿瘤切除,而后进行标准的12周期辅助FOLFOX治疗。试验开始后不久就进行了KRAS检测,旨在随机分配KRAS野生型肿瘤患者接受或不接受帕尼单抗(6周),90名符合条件的患者中有46人(31%)接受帕尼单抗。研究结果表示,与术后辅助化疗组相比,NAC使肿瘤显著的降期(P=0.04),尤其是那些有根部淋巴结浸润的患者(P<0.0001),并且有两个表现为病理完全缓解。他们还发现用NAC治疗的患者手术切缘阳性明显较低(P=0.002),并观察到明显的肿瘤消退分级(P=0.0001),而没有发生明显的围手术期发病率。

Jakobsen等人[37]研究了NAC是否能将高风险患者(需要AC的患者)转化为低风险(不需要AC)。在这项丹麦的II期随机对照试验中,77名经组织学诊断为腺癌的患者,CT扫描显示为高风险的T3或T4肿瘤,在术前分期CT上没有远处转移,根据突变状态(野生型与突变型+不明状态)分为两组。KRAS、BRAF、PIK3CA突变或突变状态不明的患者接受三个周期的新辅助治疗CAPOX(卡培他滨和奥沙利铂),而野生型患者接受同样的化疗,并辅以帕尼单抗。所有患者随后都进行了肿瘤切除手术,并在组织病理学分析后进一步分期。那些拥有高风险T3肿瘤的患者被定义为至少有以下因素之一:(I)切除标本中的淋巴结少于12个。(II)分化程度较差的肿瘤。(III)血管、淋巴或神经末梢侵犯或T4肿瘤在接受不包含帕尼单抗的5个周期的CAPOX治疗后被认为是“未转化”。该研究的主要终点是"转化"患者,比如那些不符合AC标准的患者,该组患者后续仅进行随访观察。从高风险患者到低风险患者的总体转换率在野生型组中为42%,而在有突变的患者中为51%。次要终点是复发率和无病生存(DFS)。该研究报告,转归与未转归患者的累积复发率为6%vs.32%(P=0.005),3年DFS为94%vs.63%(P=0.005)。Jakobsen等人的结论是,NAC在LACC中是可行的,并认为该研究部分结果是因为淋巴结转移的消除,对于转化率应该提醒的是,因为术前CT可能无法发现在手术切除标本中发现的淋巴结转移。

法国一项II期多中心随机对照试验(PRODIGE 22)[38]评估了NAC对局部晚期非转移性结肠癌患者的疗效和安全性。120名可切除的高危T3或T4肿瘤和(或)N2淋巴结转移的患者被随机分配到切除手术后接受八个周期的FOLFOX辅助治疗或接受四个周期的新辅助治疗FOLFOX±西妥昔单抗(取决于RAS突变状态),然后进行切除手术,随后再接受八个周期的相同化疗。重要的是,在中期分析中,FOLFOX+西妥昔单抗组由于缺乏疗效而被停止,因此该组被排除在统计分析之外。在这104名患者中,该组没有观察到NAC组肿瘤明显的病理反应(TRG1级),但他们确实发现,与对照组相比,NAC组有明显的肿瘤退缩,44% vs. 8%,P<0.001,有肿瘤降期的趋势,但总死亡率和发病率没有明显差异。

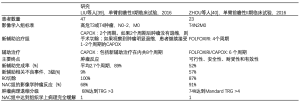

表2描述了两个中国单臂II期前瞻性试验[39,40],研究NAC在LACC中的可行性、安全性和肿瘤反应,还报道了显著的肿瘤退缩和降期,毒性和围手术期发病率均可接受。此外,多因素回归分析结果显示对接受NAC治疗的T4结肠癌患者,影像学和组织学上都有显著的肿瘤退缩[41-43]和更高的3年总存活率(OS) [44]。

Full table

在最近的2019年ESMO大会上,FOxTROT协作组提交了对英国、丹麦和瑞典的98家医院的1053名患者的中期分析[45]。在分配到NAC组的699名患者中,88%完成了三个周期的新辅助治疗FOLFOX,并且在NAC后有明显的肿瘤组织学降期,pT和pN分期降低(两者的P<0.0001)。小部分NAC组患者表现出完全(3.8%)和接近完全(4.6%)的肿瘤消退。NAC组的严重围手术期并发症、住院时间延长和再次手术率都较低。

综上所述,NAC在LACC中似乎是一种安全、可行和耐受性良好的治疗方法,目前的证据表明,尽管不断有新的研究,NAC被认为可以导致显著的肿瘤消退和降期,同时有极低的不良后果和围手术期发病率。

局部晚期结肠癌的新辅助放疗

新辅助放疗(NRT)在LACC中的作用仍不明确,虽然正在进行评估其安全性和有效性的研究[46,47],但支持其在该患者群体中使用的明确数据相对缺乏。理论上,NRT的好处包括缩小肿瘤体积和降低肿瘤细胞脱落的风险,使手术结果更有利于实现R0切除。NRT还可能具有较低的副作用和毒性,因为与纤维化的术后组织相比,健康组织的氧合作用和血液供应可以更好地渗透到肿瘤组织。有新的证据证实了这些理论上的好处。

Krishnamurty等人[48]进行了一项队列分析,以确定非转移性T4结肠癌患者接受NRT的效果。患者被分成两组,接受NRT和没有接受NRT的患者,所有患者都进行了肿瘤切除手术,主要研究终点是R0切除和总生存率(OS)。在纳入研究的131名患者中,23名患者(17.4%)接受了NRT。他们发现R0切除率和局部复发率均无统计学意义的改善,中位随访时间为52.6个月。然而,在NRT组中,肿瘤降期有统计学意义上的差异(P=0.007),5年OS有改善(P=0.03)。这项研究有几个局限性,包括样本量小、选择偏差,虽然两个队列的治疗前因素相似,但各组之间的放射技术/剂量和化疗方案不一致。此外,NRT组中91%的人接受了NAC,而非NRT组中只有3%,这可能会进一步混淆结果。

Hawkins及其同事[49]在2019年进行的一项较大的研究分析了国家癌症数据库(美国和波多黎各)中T4期LACC患者使用NRT的情况。研究中纳入了15207名接受切除手术的临床T4期患者,其中195名患者(1.3%)接受了NRT 。研究小组报告说,NRT与R0切除率无统计学差异,但对5年OS的改善有统计学差异(P<0.001)。此外,对临床T4b分期的患者进行的亚组分析显示,该组患者接受NRT后,5年OS得到改善更加显著(P=0.002)。本研究的一个主要局限是在术前分期、肿瘤位置、肿瘤扩大切除或多脏器切除所涉及的器官、放射剂量和方法以及副作用方面的数据收集不完整。由于在进行NRT之前没有进行随机化,可能存在明显的选择偏差。此外,NRT的一个关键结果是局部复发率,这个数据没有被纳入统计。

局部晚期结肠癌的新辅助放化疗

新辅助放化疗治疗LACC的报道仅见于病例报告和三个规模较小的病例系列研究[50-52]。这些研究(表3)虽然受到样本量和随访时间的严重限制,但报告了令人鼓舞的高R0切除率和病理完全缓解率。

Full table

外科手术治疗

LACC给手术带来了挑战,因为肿瘤,尤其是T4肿瘤可以扩大、粘连,甚至侵犯邻近器官。这些粘连表现出特别高的恶性风险,再加上术中对粘连性质的评估往往不准确[53],指南建议对这些肿瘤进行完整的多脏器联合切除。多项研究证实,扩大切除范围可以提高阴性切除边缘的概率,并且能改善OS[8,54,55]。

最常见的受累器官是膀胱和小肠袢[25,53,56],然而,取决于肿瘤的位置,它也可能侵入腹壁、胰十二指肠区、肝、胃、脾和(或)尿路(肾脏、输尿管)。

向前侵犯(小肠、膀胱、前列腺、精囊腺、阴道)

肿瘤侵犯小肠可以通过整段小肠切除,而侵犯结肠其他部分可能需要扩大结肠切除术,甚至是次全结肠切除术。

如果肿瘤已经侵犯膀胱,但没有远处转移,完整切除肿瘤需要对膀胱壁进行全层切除,切缘需要2-3厘米[57-59]。虽然在大多数情况下可以实现膀胱的一期重建,但应根据肿瘤的解剖位置决定进行全膀胱切除还是部分切除,大多数LACC可见肿瘤侵入膀胱顶部,只需要进行部分膀胱切除就可以确保肉眼上有足够的切缘[60],因为如果切缘为阴性,这两种手术的局部复发率和总生存率是没有太大差异的[61]。

向上侵犯(胃、十二指肠、胰腺、胆囊、脾)

对侵犯胃的T4期横结肠癌进行完整切除,包括胃大弯的楔形切除或远端胃切除,这取决于侵犯的程度[62]。侵犯脾脏的脾区结肠癌可能需要进行脾切除术,如果胰腺尾部受累的话,甚至需要脾胰腺联合切除术[63],而侵犯肝脏的肝区结肠癌可能需要进行胆囊切除术和楔形或分段肝切除术[62,64]。横结肠偏右侧的结肠癌可以侵入十二指肠和(或)胰头,因此在手术上有一定的难度。如果可能的话,局限的十二指肠侵犯一般需要进行十二指肠部分切除术,并进行一期吻合,或者在缺损过大时进行十二指肠空肠造口术[65]。当胰头受累时,则需要接受根治性胰十二指肠切除术[66]。

向后侵犯(大血管、肾脏、输尿管)

侵犯肠系膜上动脉或髂总动脉的肿瘤通常被认为是不能切除的[67],然而,随着近年来血管移植、股-股动脉旁路术和一期血管吻合术的发展,这种情况已不再是绝对禁忌[68]。右侧或左侧T4结肠癌可以侵入肾脏和(或)输尿管,这可以通过全肾切除和(或)输尿管切除术解决[69,70]。如果对侧肾脏功能异常,可以进行输尿管-输尿管吻合术[71],如果有足够的输尿管剩余长度,并且在肿瘤扩大切除范围中没有必要进行肾脏切除,通过Boari皮瓣将输尿管重新植入膀胱,无论是否进行腰大肌悬吊,都可以维持基本的肾功能[71,72]。

腹膜侵犯

对于部分腹膜转移量较低患者,NCCN建议考虑减瘤手术和腹腔温热化疗(HIPEC)[8]。这主要是基于Verwaal等人[73]的一项随机对照试验的结果,该试验评估了单独使用5-氟尿嘧啶(5-FU)全身化疗与减瘤手术合并使用丝裂霉素C的HIPEC,该小组证明,与单独用药的全身治疗相比,接受减瘤手术和HIPEC的患者的生存期增加了一倍(22.3个月与12.6个月)。有争议的PRODIGE 7试验[74]比较了减瘤手术加HIPEC和围手术期奥沙利铂治疗和单纯的减瘤手术,虽然研究小组在减瘤手术和HIPEC中加入围手术期奥沙利铂没有达到OS的主要终点,但他们确实发现,单独的减瘤手术已经可以显示出令人满意的OS,而加入HIPEC有可能推迟首次复发时间。

局部晚期结肠癌的辅助放疗

辅助放疗在LACC中的作用并不明确,到目前为止,只有一项随机对照试验(Intergroup-0130)[47]试图评估辅助化疗联合放疗与单独辅助化疗在LACC患者中的作用。不幸的是,该试验因招募患者不足而提前终止。然而,该研究显示,两组患者的5年OS和DFS相当,化疗合并放疗组患者的副作用更高。Sebastian等人[75]最近进行的一项规模较大的回顾性队列分析研究发现,T4结肠癌患者接受或不接受辅助放疗的OS没有统计学上的差异,但同时认为它可能对那些T4b病变和(或)切除后的切缘阳性的患者有益,一些较小的回顾性观察研究也进一步证实了这一点[46,76]。

总结

尽管近年来影像学检查在术前分期方面取得了长足的进步,但T4期结肠癌的准确诊断仍然是一项艰巨的任务,这是因为有相当比例的患者会出现急性肠梗阻或肿瘤穿孔,而这些情况通过影像学检查无法准确预测恶性肿瘤真实的侵袭程度。越来越多的文献定义了新辅助化疗和放疗在提高R0切除率和T4期结肠癌生存率方面的作用,然而,NCCN或ESMO指南尚未广泛推荐。对于T4期结肠癌来说,扩大的多脏器联合广泛切除是必须的,而且术后的发病率和死亡率也是可以接受的,因为达到R0切除就有机会达到治愈的效果。

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Provenance and Peer Review: This article was commissioned by the Guest Editor (Eva Segelov) for the series “Colorectal Cancer” published in Digestive Medicine Research. The article has undergone external peer review.

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the Narrative Review reporting checklist. Available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/dmr-20-74

Peer Review File: Available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/dmr-20-74

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/dmr-20-74). The series “Colorectal Cancer” was commissioned by the editorial office without any funding or sponsorship. The authors have no other conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Xue L, Williamson A, Gaines S, et al. An update on colorectal cancer. Curr Probl Surg 2018;55:76-116. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Larkin JO, O'Connell PR. Multivisceral resection for T4 or recurrent colorectal cancer. Dig Dis 2012;30:96-101. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, Goding Sauer A, et al. Colorectal cancer statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J Clin 2020;70:145-64. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ueno H, Mochizuki H, Akagi Y, et al. Optimal colorectal cancer staging criteria in TNM classification. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:1519-26. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gao P, Song YX, Wang ZN, et al. Is the prediction of prognosis not improved by the seventh edition of the TNM classification for colorectal cancer? Analysis of the surveillance, epidemiology, and end results (SEER) database. BMC Cancer 2013;13:123.

- Edge SB, Compton CC. The American Joint Committee on Cancer: the 7th edition of the AJCC cancer staging manual and the future of TNM. Ann Surg Oncol 2010;17:1471-4.

- Pellino G, Warren O, Mills S, et al. Comparison of Western and Asian Guidelines concerning the management of colon cancer. Dis Colon Rectum 2018;61:250-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Benson AB, Venook AP, Al-Hawary MM, et al. NCCN guidelines insights: colon cancer, version 2.2018. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2018;16:359-69. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Grossmann I, Klaase JM, Avenarius JK, et al. The strengths and limitations of routine staging before treatment with abdominal CT in colorectal cancer. BMC Cancer 2011;11:433. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nerad E, Lahaye MJ, Maas M, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of CT for local staging of colon cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2016;207:984-95. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dighe S, Purkayastha S, Swift I, et al. Diagnostic precision of CT in local staging of colon cancers: a meta-analysis. Clin Radiol 2010;65:708-19. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Takano S, Kato J, Yamamoto H, et al. Identification of risk factors for lymph node metastasis of colorectal cancer. Hepatogastroenterology 2007;54:746-50. [PubMed]

- Engelmann BE, Loft A, Kjaer A, et al. Positron emission tomography/computed tomography for optimized colon cancer staging and follow up. Scand J Gastroenterol 2014;49:191-201. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Balyasnikova S, Brown G. Optimal imaging strategies for rectal cancer staging and ongoing management. Curr Treat Options Oncol 2016;17:32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dam C, Lindebjerg J, Jakobsen A, et al. Local staging of sigmoid colon cancer using MRI. Acta Radiol Open 2017;6:2058460117720957. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hunter C, Siddiqui M, Georgiou Delisle T, et al. CT and 3-T MRI accurately identify T3c disease in colon cancer, which strongly predicts disease-free survival. Clin Radiol 2017;72:307-15. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Liu LH, Lv H, Wang ZC, et al. Performance comparison between MRI and CT for local staging of sigmoid and descending colon cancer. Eur J Radiol 2019;121:108741. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nerad E, Lambregts DM, Kersten EL, et al. MRI for local staging of colon cancer: can MRI become the optimal staging modality for patients with colon cancer? Dis Colon Rectum 2017;60:385-92. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Park SY, Cho SH, Lee MA, et al. Diagnostic performance of MRI- versus MDCT-categorized T3cd/T4 for identifying high-risk stage II or stage III colon cancers: a pilot study. Abdom Radiol (NY) 2019;44:1675-85. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Koopman M, Kortman GA, Mekenkamp L, et al. Deficient mismatch repair system in patients with sporadic advanced colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer 2009;100:266-73. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Loupakis F, Cremolini C, Masi G, et al. Initial therapy with FOLFOXIRI and bevacizumab for metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med 2014;371:1609-18. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Blons H, Emile JF, Le Malicot K, et al. Prognostic value of KRAS mutations in stage III colon cancer: post hoc analysis of the PETACC8 phase III trial dataset. Ann Oncol 2014;25:2378-85. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bokemeyer C, Bondarenko I, Hartmann JT, et al. Efficacy according to biomarker status of cetuximab plus FOLFOX-4 as first-line treatment for metastatic colorectal cancer: the OPUS study. Ann Oncol 2011;22:1535-46. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ohhara Y, Fukuda N, Takeuchi S, et al. Role of targeted therapy in metastatic colorectal cancer. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2016;8:642-55. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lehnert T, Methner M, Pollok A, et al. Multivisceral resection for locally advanced primary colon and rectal cancer: an analysis of prognostic factors in 201 patients. Ann Surg 2002;235:217-25. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Croner RS, Merkel S, Papadopoulos T, et al. Multivisceral resection for colon carcinoma. Dis Colon Rectum 2009;52:1381-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nelson H, Petrelli N, Carlin A, et al. Guidelines 2000 for colon and rectal cancer surgery. J Natl Cancer Inst 2001;93:583-96. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bosset JF, Calais G, Mineur L, et al. Enhanced tumorocidal effect of chemotherapy with preoperative radiotherapy for rectal cancer: preliminary results--EORTC 22921. J Clin Oncol 2005;23:5620-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- de Bruin AF, Nuyttens JJ, Ferenschild FT, et al. Preoperative chemoradiation with capecitabine in locally advanced rectal cancer. Neth J Med 2008;66:71-6. [PubMed]

- Sauer R, Becker H, Hohenberger W, et al. Preoperative versus postoperative chemoradiotherapy for rectal cancer. N Engl J Med 2004;351:1731-40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gérard JP, Conroy T, Bonnetain F, et al. Preoperative radiotherapy with or without concurrent fluorouracil and leucovorin in T3-4 rectal cancers: results of FFCD 9203. J Clin Oncol 2006;24:4620-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Allum WH, Stenning SP, Bancewicz J, et al. Long-term results of a randomized trial of surgery with or without preoperative chemotherapy in esophageal cancer. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:5062-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cunningham D, Allum WH, Stenning SP, et al. Perioperative chemotherapy versus surgery alone for resectable gastroesophageal cancer. N Engl J Med 2006;355:11-20. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Maas M, Nelemans PJ, Valentini V, et al. Long-term outcome in patients with a pathological complete response after chemoradiation for rectal cancer: a pooled analysis of individual patient data. Lancet Oncol 2010;11:835-44. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Eltahir A, Heys SD, Hutcheon AW, et al. Treatment of large and locally advanced breast cancers using neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Am J Surg 1998;175:127-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Foxtrot Collaborative Group. Feasibility of preoperative chemotherapy for locally advanced, operable colon cancer: the pilot phase of a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol 2012;13:1152-60. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jakobsen A, Andersen F, Fischer A, et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy in locally advanced colon cancer. A phase II trial. Acta Oncol 2015;54:1747-53. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Karoui M, Rullier A, Piessen G, et al. Perioperative FOLFOX 4 versus FOLFOX 4 plus cetuximab versus immediate surgery for high-risk stage II and III colon cancers: a phase II multicenter randomized controlled trial (PRODIGE 22). Ann Surg 2020;271:637-45. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Liu F, Yang L, Wu Y, et al. CapOX as neoadjuvant chemotherapy for locally advanced operable colon cancer patients: a prospective single-arm phase II trial. Chin J Cancer Res 2016;28:589-97. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhou H, Song Y, Jiang J, et al. A pilot phase II study of neoadjuvant triplet chemotherapy regimen in patients with locally advanced resectable colon cancer. Chin J Cancer Res 2016;28:598-605. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- de Gooyer JM, Verstegen MG, 't Lam-Boer J, et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy for locally advanced T4 colon cancer: a nationwide propensity-score matched cohort analysis. Dig Surg 2020;37:292-301. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Arredondo J, Baixauli J, Pastor C, et al. Mid-term oncologic outcome of a novel approach for locally advanced colon cancer with neoadjuvant chemotherapy and surgery. Clin Transl Oncol 2017;19:379-85. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Arredondo J, Gonzalez I, Baixauli J, et al. Tumor response assessment in locally advanced colon cancer after neoadjuvant chemotherapy. J Gastrointest Oncol 2014;5:104-11. [PubMed]

- Dehal A, Graff-Baker AN, Vuong B, et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy improves survival in patients with clinical T4b colon cancer. J Gastrointest Surg 2018;22:242-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Morton D. FOxTROT: An international randomised controlled trial in 1053 patients evaluating neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC) for colon cancer. On behalf of the FOxTROT Collaborative Group. Ann Oncol 2019;30:V198. [Crossref]

- Ludmir EB, Arya R, Wu Y, et al. Role of adjuvant radiotherapy in locally advanced colonic carcinoma in the modern chemotherapy era. Ann Surg Oncol 2016;23:856-62. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Martenson JA Jr, Willett CG, Sargent DJ, et al. Phase III study of adjuvant chemotherapy and radiation therapy compared with chemotherapy alone in the surgical adjuvant treatment of colon cancer: results of intergroup protocol 0130. J Clin Oncol 2004;22:3277-83. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Krishnamurty DM, Hawkins AT, Wells KO, et al. Neoadjuvant radiation therapy in locally advanced colon cancer: a cohort analysis. J Gastrointest Surg 2018;22:906-12. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hawkins AT, Ford MM, Geiger TM, et al. Neoadjuvant radiation for clinical T4 colon cancer: A potential improvement to overall survival. Surgery 2019;165:469-75. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Huang CM, Huang MY, Ma CJ, et al. Neoadjuvant FOLFOX chemotherapy combined with radiotherapy followed by radical resection in patients with locally advanced colon cancer. Radiat Oncol 2017;12:48. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Qiu B, Ding PR, Cai L, et al. Outcomes of preoperative chemoradiotherapy followed by surgery in patients with unresectable locally advanced sigmoid colon cancer. Chin J Cancer 2016;35:65. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cukier M, Smith AJ, Milot L, et al. Neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy and multivisceral resection for primary locally advanced adherent colon cancer: a single institution experience. Eur J Surg Oncol 2012;38:677-82. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gezen C, Kement M, Altuntas YE, et al. Results after multivisceral resections of locally advanced colorectal cancers: an analysis on clinical and pathological t4 tumors. World J Surg Oncol 2012;10:39. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Otchy D, Hyman NH, Simmang C, et al. Practice parameters for colon cancer. Dis Colon Rectum 2004;47:1269-84. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tjandra JJ, Kilkenny JW, Buie WD, et al. Practice parameters for the management of rectal cancer (revised). Dis Colon Rectum 2005;48:411-23. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- López-Cano M, Mañas MJ, Hermosilla E, et al. Multivisceral resection for colon cancer: analysis of prognostic factors. Dig Surg 2010;27:238-45. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Woranisarakul V, Ramart P, Phinthusophon K, et al. Accuracy of preoperative urinary symptoms, urinalysis, computed tomography and cystoscopic findings for the diagnosis of urinary bladder invasion in patients with colorectal cancer. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2014;15:7241-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Delacroix SE Jr, Winters JC. Bladder reconstruction and diversion during colorectal surgery. Clin Colon Rectal Surg 2010;23:113-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fujisawa M, Nakamura T, Ohno M, et al. Surgical management of the urinary tract in patients with locally advanced colorectal cancer. Urology 2002;60:983-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Carne PW, Frye JN, Kennedy-Smith A, et al. Local invasion of the bladder with colorectal cancers: surgical management and patterns of local recurrence. Dis Colon Rectum 2004;47:44-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Talamonti MS, Shumate CR, Carlson GW, et al. Locally advanced carcinoma of the colon and rectum involving the urinary bladder. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1993;177:481-7. [PubMed]

- Kapoor S, Das B, Pal S, et al. En bloc resection of right-sided colonic adenocarcinoma with adjacent organ invasion. Int J Colorectal Dis 2006;21:265-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Diaconescu M, Burada F, Mirea CS, et al. T4 colon cancer - current management. Curr Health Sci J 2018;44:5-13. [PubMed]

- Qu K, Liu C, Mansoor AM, et al. Pyogenic liver abscess as initial presentation in locally advanced right colon cancer invading the liver, gallbladder, and duodenum. Front Med 2011;5:434-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cirocchi R, Partelli S, Castellani E, et al. Right hemicolectomy plus pancreaticoduodenectomy vs partial duodenectomy in treatment of locally advanced right colon cancer invading pancreas and/or only duodenum. Surg Oncol 2014;23:92-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhang J, Leng JH, Qian HG, et al. En bloc pancreaticoduodenectomy and right colectomy in the treatment of locally advanced colon cancer. Dis Colon Rectum 2013;56:874-80. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shibata D, Paty PB, Guillem JG, et al. Surgical management of isolated retroperitoneal recurrences of colorectal carcinoma. Dis Colon Rectum 2002;45:795-801. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Abdelsattar ZM, Mathis KL, Colibaseanu DT, et al. Surgery for locally advanced recurrent colorectal cancer involving the aortoiliac axis: can we achieve R0 resection and long-term survival? Dis Colon Rectum 2013;56:711-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Stief CG, Jonas U, Raab R. Long-term follow-up after surgery for advanced colorectal carcinoma involving the urogenital tract. Eur Urol 2002;41:546-50. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Stief CG, Raab R. Interdisciplinary abdomino-urological surgery for advanced colorectal carcinoma involving the urogenital tract. BJU Int 2002;89:496-503. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Elenkov C, Draganov K, Donkov I, et al. Extrinsic obstruction of the ureter in colorectal cancer--aspects of pathogenesis, diagnosis and treatment. Khirurgiia (Sofiia) 2006;36-40. [PubMed]

- Lazar AM, Bratucu E, Straja ND, et al. Primitive retroperitoneal tumors. Vascular involvement--a major prognostic factor. Chirurgia (Bucur) 2012;107:186-94. [PubMed]

- Verwaal VJ, van Ruth S, de Bree E, et al. Randomized trial of cytoreduction and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy versus systemic chemotherapy and palliative surgery in patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis of colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 2003;21:3737-43. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Quénet F. Colorectal peritoneal carcinomatosis: what is the future of HIPEC? Eur J Surg Oncol 2018;44:1847-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sebastian NT, Tan Y, Miller ED, et al. Surgery with and without adjuvant radiotherapy is associated with similar survival in T4 colon cancer. Colorectal Dis 2020;22:779-89. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Willett CG, Fung CY, Kaufman DS, et al. Postoperative radiation therapy for high-risk colon carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 1993;11:1112-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

冯雯卿

医学博士,上海交通大学医学院附属瑞金医院普外科博士后,毕业于上海交通大学医学院临床医学八年制专业, 2020年至今工作于上海交通大学医学院附属瑞金医院普外科博士后工作站,从事结直肠肿瘤以及肿瘤免疫微环境相关研究。(更新时间:2021/8/5)

(本译文仅供学术交流,实际内容请以英文原文为准。)

Cite this article as: Gosavi R, Heriot AG, Warrier SK. Current management and controversies in management of T4 cancers of the colon—a narrative review of the literature. Dig Med Res 2020;3:67.